Newsletter

August 2020

From Our Director

Reset: Fostering Marine Justice and a Truly Sustainable Blue Ocean Economy

We are all witnessing rapid environmental improvements linked to the cessation of economic offshore and coastal activity, reminding us of the significant impact of how we choose to live and the interconnectedness of our society and the environment. At the same time, people are facing the pandemic, widespread unemployment, and calls for greater equity and racial justice. While these issues appear to be far removed from UCI’s day-to-day work, we recognize that environmental justice and communities of color bear a disproportionate share of the burden of marine pollution, coastal storms and sea level rise, as well as uneven access to and distribution of benefits from the ocean. We have been reminded that in order to support an ocean that will thrive and benefit future generations, we need to step back, broaden our lens, and design more ambitious and inclusive solutions.

In 2017, the UCI hosted a Mid-Atlantic Blue Ocean Economy 2030 symposium, where we sought to develop a road map for a truly sustainable blue ocean economy. The importance of imagining a future that is just, as well as sustainable, is more urgent than ever. A return to business as usual will not be sufficient to meet the challenges we face. There is an opportunity to go beyond a short-term response and recovery to resetting systems for the long term that fully recognize the links between ocean ecosystems, economies and societies. As part of that reset, consideration of diversity, equity, inclusion and justice both reflects the UCI’s core values and provides guideposts for informing community recovery, social responsibility and marine conservation options.

Recognizing these interconnections, there is an emerging concept of ocean or marine justice, where social equity, marine science and conservation intersect. It calls for consideration and study of the human dimension, as well as natural systems. In New Jersey, our connections with the sea and shore are tied intimately with our history, community well-being and a strong sense of place. How can we take that into account as we consider plans for economic recovery? How can we incorporate these broad perspectives and consideration of fair distribution of benefits with particular attention to the most vulnerable?

The UCI and academia have a special responsibility to step up to try to break down the barriers across areas of study and to work with diverse communities to answer these questions. Marine and ocean studies programs present particular challenges for increasing diversity, equity, inclusivity, and justice and belonging. There is a lack of diversity in ocean science programs, leadership and faculty. Training may occur at small coastal field stations embedded in communities that are not very diverse or socially integrated.

I am fortunate to be working with colleagues at Monmouth and on the National Academy of Sciences Ocean Studies Board, where we are discussing these issues and considering what it would look like for ocean studies to be diverse, equitable, inclusive, just, and foster a sense of belonging. At the UCI, we put out a special call to fund grants this year to support faculty and student research and community-based projects focused on bold ideas for sustainably rebuilding communities and economies while addressing disproportionate needs of our most vulnerable populations. There is much to be gained by building a more diverse and inclusive community that joins together collectively as a steward of the ocean and shares in its bounty.

Tony MacDonald

Urban Coast Institute Director

UCI Marine Scientist Assists with Humpback Whale Rescue

UCI Marine Scientist Jim Nickels responded to an emergency call aboard Monmouth University’s research vessel Heidi Lynn Sculthorpe on July 30 to help free a humpback whale entangled in a commercial trawl net off Long Island.

Officials from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), Army Corps of Engineers, New York State Department of Environmental Conservation, Atlantic Marine Conservation Society, U.S. Coast Guard, Center for Coastal Studies (CCS) and Turtles Fly Too all collaborated to free the animal. The effort began on July 27, when the Coast Guard received a report of a distressed whale in the Ambrose Channel of New York. Nickels was joined aboard the Heidi Lynn Sculthorpe on Thursday by Monmouth University graduate Peter Plantamura of the NOAA Northeast Fisheries Science Center’s (NEFSC) Sandy Hook lab.

The humpback was essentially anchored in place by what NOAA estimated to be nearly 4,000 pounds of netting, ropes and steel cables wrapped around its tail. Nickels said by the time he arrived, the whale appeared in mortal danger.

“It was a massive commercial net and the whale was in a nasty tangle,” Nickels said. “It was to the point where it was having trouble breathing.”

The Heidi Lynn Sculthorpe’s net reel was used to lift up the gear enough to relieve the pressure on the whale and allow it to move and breathe easier. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers Drift Collection Vessel HAYWARD’s crain then pulled the gear out of the water and the CCS team cut through it until the whale could swim free.

A press release recounting the full four-day rescue was issued by NOAA on behalf of all of the rescue partners. The whale has since been spotted swimming safely off the coast of Long Island.

Additional Coverage

Additional Coverage

Distressed, entangled humpback whale off New York set free, WPIX 11

Entangled humpback whale rescued from New York channel, National Fisherman

Humpback Whale Near NYC Successfully Freed After Days Of “Fighting To Live,” Gothamist

Who Lives in the Lower Hudson-Raritan Estuary? Comparing Net Results, Genetics

Professors Jason Adolf, Keith Dunton, and John Tiedemann are taking the Census. Clipboards in hand, they and a crew of student researchers stop by some of the Monmouth County Bayshore’s most diverse neighborhoods, collecting information that will help build a clearer picture of who lives there. On this day, we learn the area has high populations of Northern pufferfish, squid, butterfish, sea robins and spider crabs.

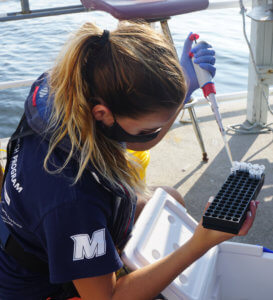

The team also has a way to learn about those who weren’t seen at the time of the visit. Water samples taken at the scene will be lab tested for trace genetic material, known as environmental DNA (eDNA), that can identify marine organisms which may or may not have been caught in their nets.

The team also has a way to learn about those who weren’t seen at the time of the visit. Water samples taken at the scene will be lab tested for trace genetic material, known as environmental DNA (eDNA), that can identify marine organisms which may or may not have been caught in their nets.

“You ask the question, do the fish that I saw in the trawl match the fish that the DNA sequence turns up?” said Adolf, endowed associate professor of marine science at Monmouth University. “Do the phytoplankton that I saw in the microscope match the phytoplankton that the DNA sequences turn up? Do the benthic invertebrates that we caught in the grab sampler match what we saw in the DNA?”

The answers will not only yield important information about marine life in Sandy Hook and Raritan bays, but for Monmouth University’s continuing exploration on the utility of eDNA as a tool for taking inventories of ecosystem fisheries and wildlife.

The answers will not only yield important information about marine life in Sandy Hook and Raritan bays, but for Monmouth University’s continuing exploration on the utility of eDNA as a tool for taking inventories of ecosystem fisheries and wildlife.

On Aug. 11, Adolf, students Skyler Post and Bryce McCall, Tiedemann, Dunton and UCI Marine Scientist Jim Nickels sampled six sites from the tip of Sandy Hook to the mouth of the Raritan River. Although only a few miles apart, the habitats at these stations can vary widely. The Lower Hudson-Raritan Estuary (to which Sandy Hook and Raritan bays belong) experiences a constant intermixing of saltwater, suburban rivers like the Navesink and Shrewsbury, industrially developed bodies such as the Arthur Kill and Hudson River, and numerous other New York-New Jersey tributaries. The floor at some stations are sandy, while others are muddy or rocky.

In addition to marine life data, the team records oceanographic parameters such as salinity, dissolved oxygen, pH, temperature, clarity, and phytoplankton biomass. Each can be indicators of the general health of the waters. Through the day’s sampling, the group learned of a large phytoplankton bloom centered along the transect between Raritan Bay and the tip of Sandy Hook, and hypoxic bottom waters (waters without sufficient oxygen to support most marine life) toward the western portion of the transect.

The water samples for eDNA analysis are run through filters, frozen and handed over to UCI Marine Genetics Faculty Fellow Megan Phifer-Rixey for analysis. This semester, she and students Cameron Gaines and Lilia Crew will extract the DNA and compare it to a database of genetic barcodes for other organisms, looking for matches.

“There’s usually quite a bit of DNA in the water samples we get from the trawls,” Phifer-Rixey said. “There’s a lot of life out there.”

With grant funding from the Achelis & Bodman Foundation, the project’s principal investigators, Adolf, Dunton and Phifer-Rixey, will conduct a half-dozen research cruises through the fall of 2021 at the same locations, building a foundation of data that can be used to detect important trends over time. Adolf said he’d like to continue the work well beyond the grant period so Monmouth will one day have decades of this data to draw upon.

“A time series is like a garden. You start small, you hope for something, and over time you watch it produce more and more results,” Adolf said. “I’d like to do six cruises per year for the rest of my career at Monmouth. This generates the kind of data needed to understand the effects of climate and anthropogenic change on marine systems, and provides ongoing opportunities for Monmouth students to become involved in established research projects.”

“A time series is like a garden. You start small, you hope for something, and over time you watch it produce more and more results,” Adolf said. “I’d like to do six cruises per year for the rest of my career at Monmouth. This generates the kind of data needed to understand the effects of climate and anthropogenic change on marine systems, and provides ongoing opportunities for Monmouth students to become involved in established research projects.”

Click here to view an album of photos from the cruise. For more on eDNA, see the proceedings of the National Conference on Marine Environmental DNA hosted by Rockefeller University Program for the Human Environment and the UCI.

Watch: Prof. Sterrett & Students Conduct Takanassee Lake Turtle Research

The UCI checked in with Monmouth University Assistant Professor Sean Sterrett and students Angel Ireland and Sara Grouleff as they conducted research on turtle populations in Long Branch’s Takanassee Lake. Among the team’s findings, a common pet species that is not native to New Jersey is now perhaps the most widespread in the system. The group’s research was supported through the UCI’s Heidi Lynn Sculthorpe Summer Research Program.

Trip Diary: Hurricane Research Gliders Launched from Monmouth Vessel

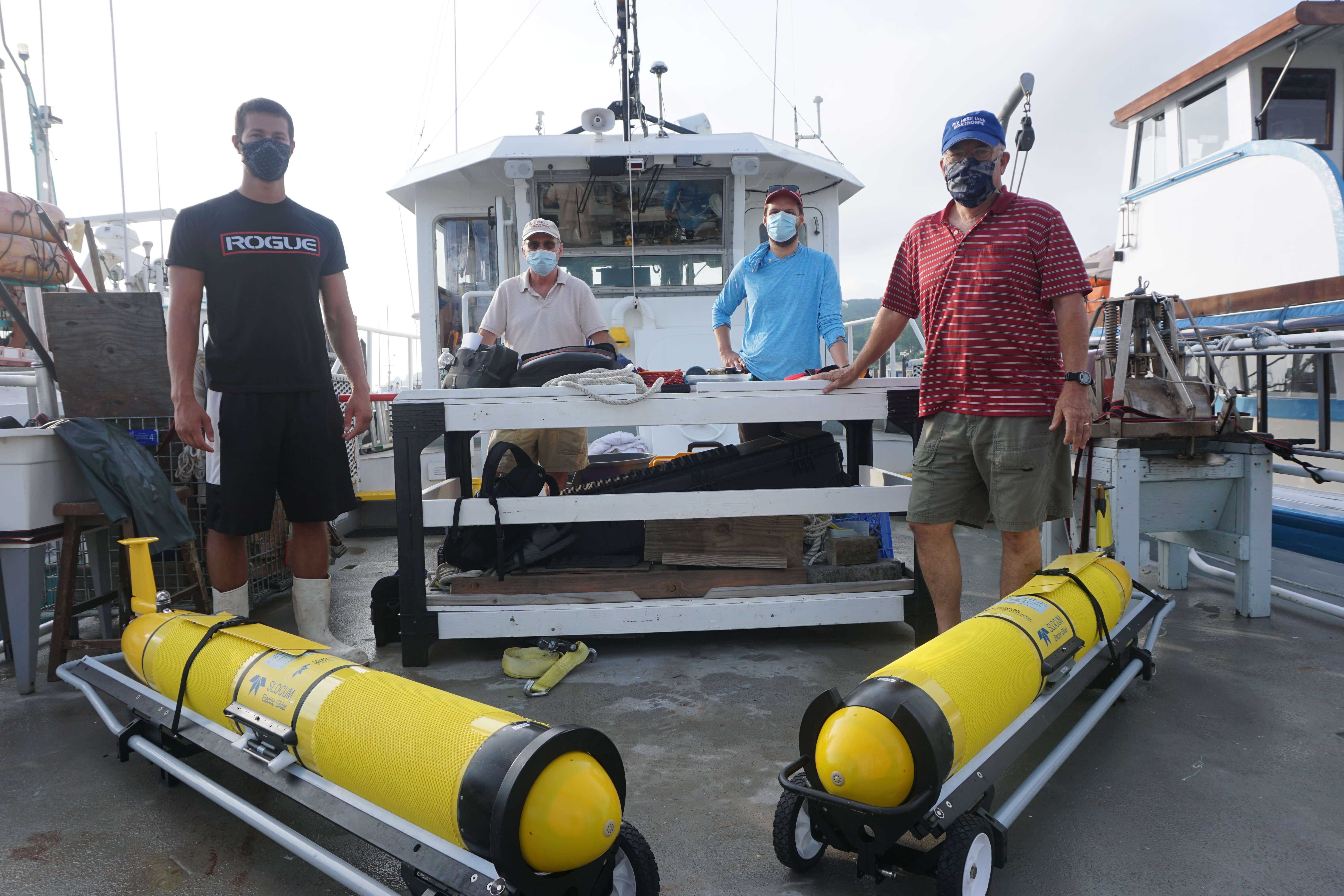

With the 2020 hurricane season officially underway, the UCI partnered with a team of federal agencies and research institutions to deploy a pair of Navy research gliders that will shed new light on the interactions between the ocean and powerful storms that pass through the New York Bight.

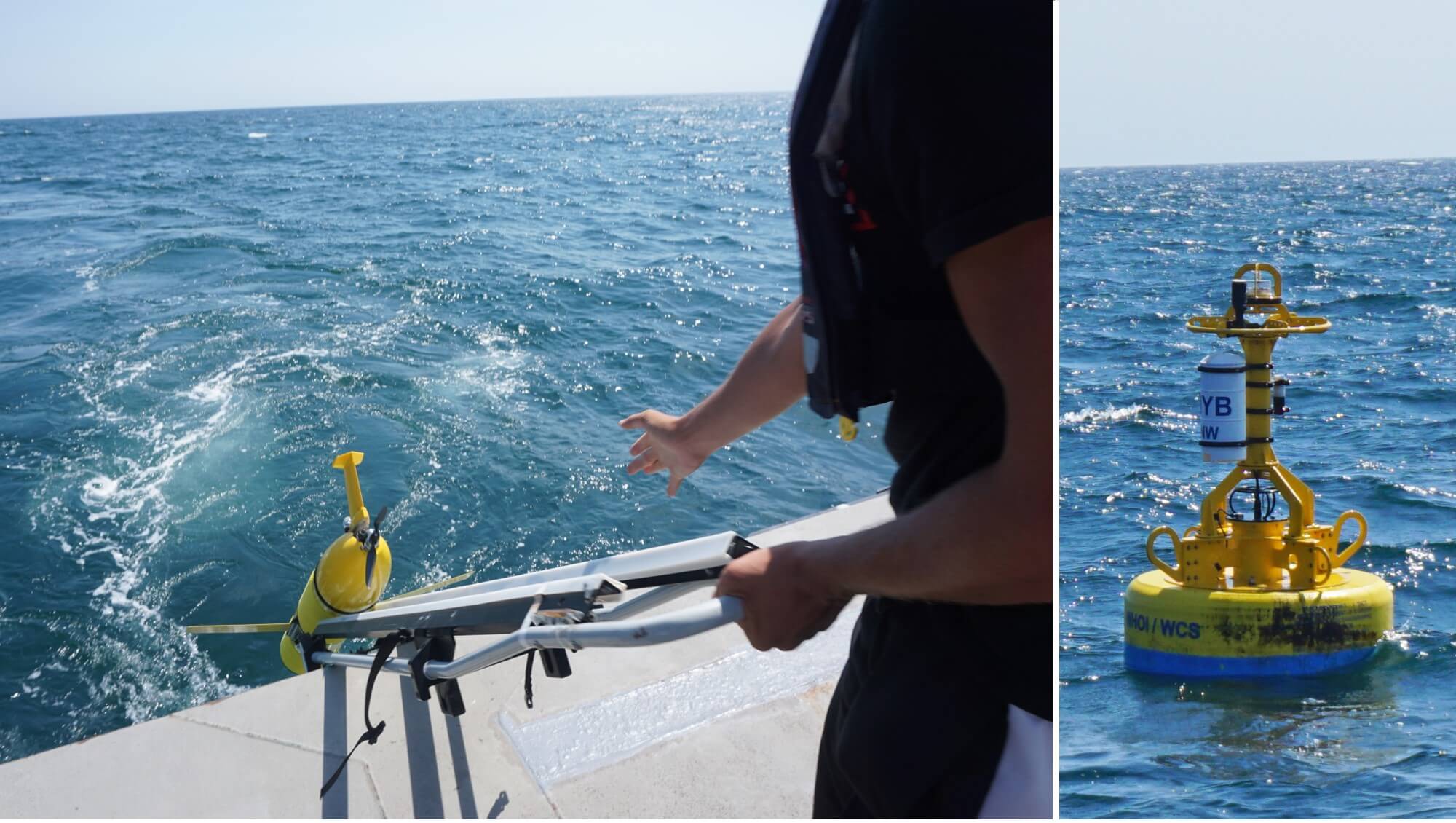

The gliders were launched from Monmouth University’s research vessel Heidi Lynn Sculthorpe at locations between the shipping lanes that approach New York Harbor. The crew included (seen above from l-r) Monmouth student Bryce McCall, Rutgers University scientists Scott Glenn and Travis Miles, UCI Marine Scientist Jim Nickels, and (not pictured) UCI Communications Director Karl Vilacoba.

The gliders will cruise the waters between the continental shelf and the coast from now through late October, collecting data on water conditions and transmitting it to scientists on the shore. Of particular interest is the influence that cooler waters at the bottom of the ocean have on storms once they “upwell,” or rise to mix with warmer surface waters as the ocean churns. Warm waters are known to fuel hurricanes, but the full degree with which colder waters slow and dissipate the storms is still under study. The gliders enable the researchers to safely measure those dynamics directly from the violent, roiling waters beneath a hurricane, and ultimately improve storm modeling. Scroll below to learn more with our photographic trip diary.

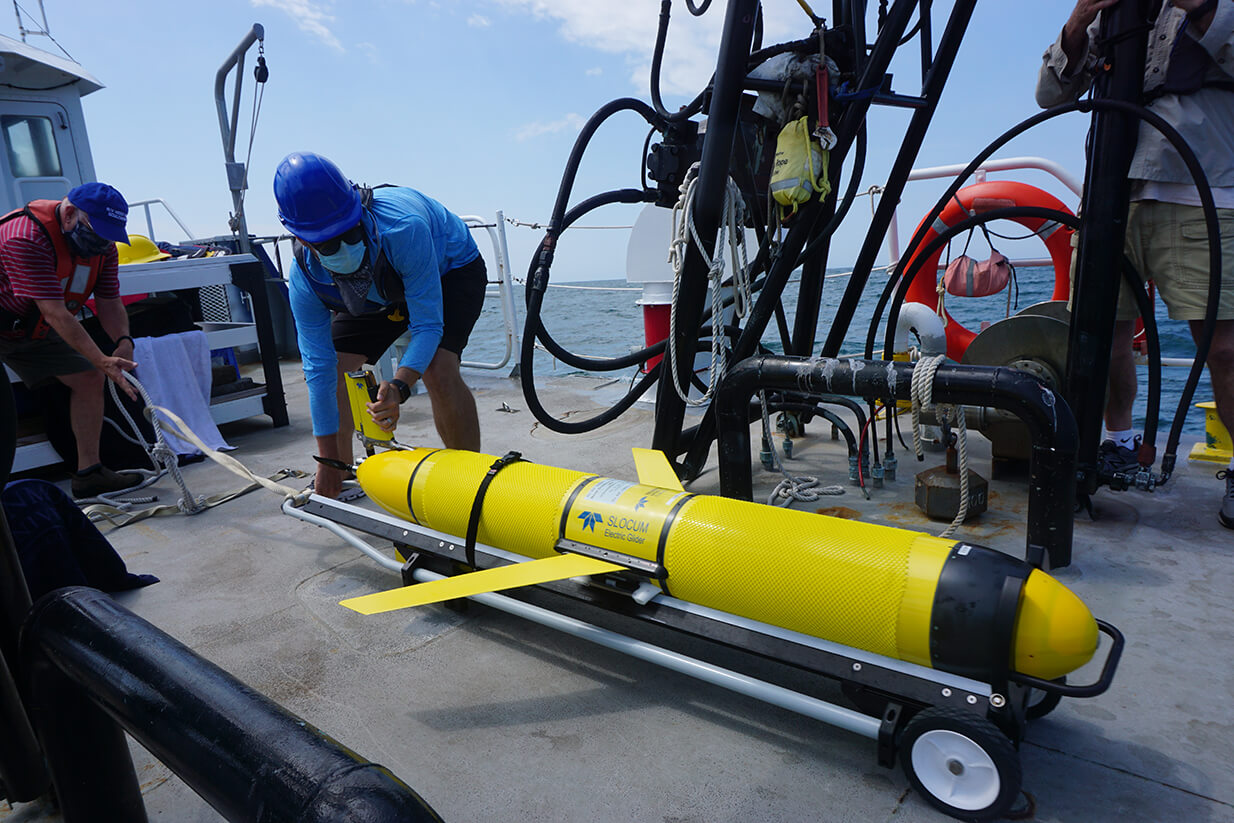

Above, Miles gets set to deploy the first glider roughly 20 miles east of Asbury Park, New Jersey. He’ll wheel the equipment to the edge of the vessel using a special hand truck with rails, angle it downward, and release the torpedo-shaped glider to plunge into the sea. It will quickly float back to the surface.

With eyes on the glider, the team will use a satellite phone to call the Naval Oceanographic Office at the John C. Stennis Space Center in Mississippi. From that site over 1,000 miles away, researchers can command the drone to carry out a battery of tests, including dives, timed cruises and data collection.

In the meantime, the team will take some readings in the water with their own equipment to make sure the glider’s data is matching up accurately. Once all of the tests were passed, the Heidi Lynn Sculthorpe headed to its next stop an hour north.

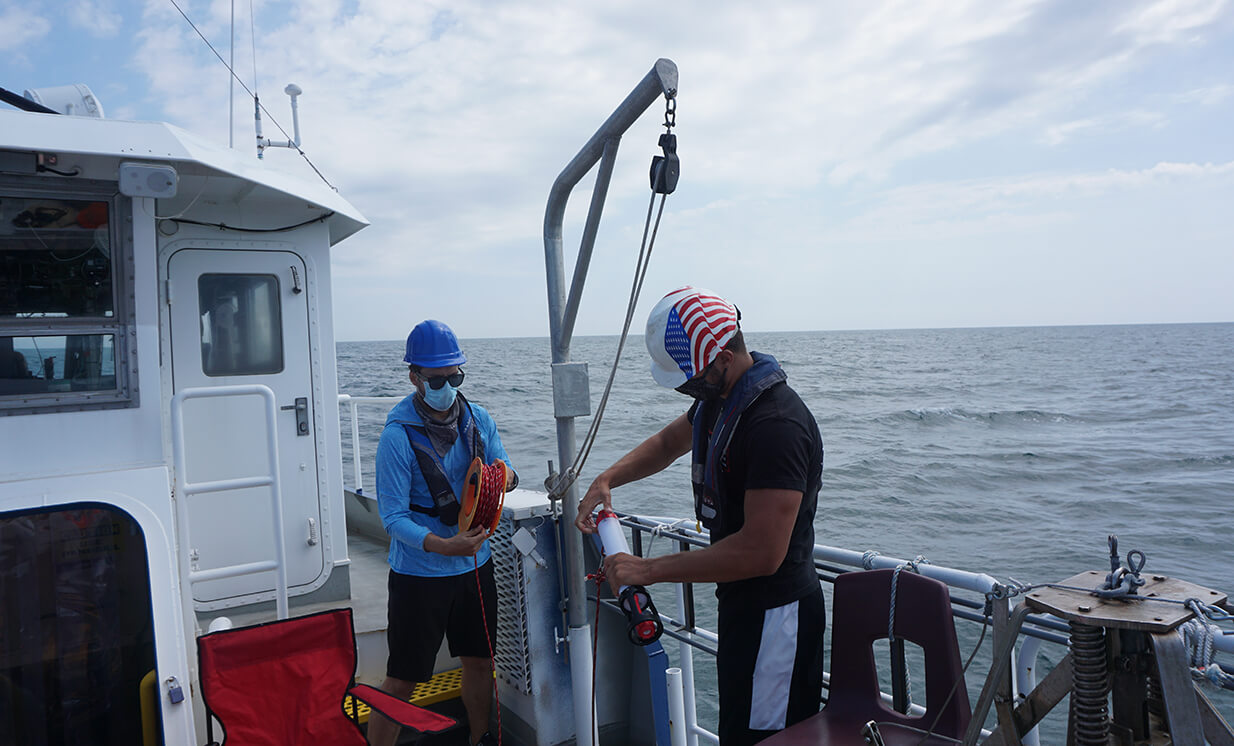

McCall launched the second glider about 15 miles south of Jones Beach, Long Island. From this point, the New York skyline and the high rises of Long Branch and Asbury Park were no longer in view. But over the next few years, these waters will be home to an installation of massive wind turbines that could produce enough renewable energy to power 1 million homes. While sailing, the crew came upon one deep-water buoy (above right) owned by the Wildlife Conservation Society and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution, used to gather scientific data.

As the Heidi Lynn Sculthorpe embarked on its 3-hour trip back to Atlantic Highlands, the waters suddenly grew rough and Capt. Nickels’ radio buzzed with warnings to mariners. The 100-degree, ultra-humid air was about to burst open with thunderstorms and 40 knot winds. Nearing Sandy Hook, the crew was treated to a dazzling show of fork lighting and ominous cloud formations over New York City.

The glider deployment was carried out under the auspices of the Mid-Atlantic Regional Association Coastal Ocean Observing System (MARACOOS). Several other gliders were launched at other locations along the Atlantic Coast as part of the multi-year project. Additional partners include the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), the Integrated Ocean Observing System (IOOS) and several other academic institutions.

Watch our video below chronicling last year’s glider deployment aboard the Heidi Lynn Sculthorpe.

Report by Monmouth, NJDEP Touts Nature Restoration for Coastal Resilience

Monmouth University researchers, in partnership with the New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP), recently completed a report that offers guidance for determining the appropriate type and location of green infrastructure projects designed to improve the resilience of coastal communities and ecosystems. The report, Framework for a Coastal Ecological Adaptation Prioritization Support Tool: Methodology, was authored by Urban Coast Institute (UCI) Director Thomas Herrington and History and Anthropology Department Associate Professor Geoff Fouad.

The research stemmed from a 2015 NJDEP effort to create a guidebook for communities implementing natural and nature-based adaptations in coastal areas. Natural adaptations focus on conserving and restoring existing features (for example, planting grasses on beach dunes) while nature-based adaptations are hybrid, engineered approaches that seek to mimic the risk reduction functions of natural systems (such as depositing dredged sediments in a bay to create an artificial island). The NJDEP developed 10 successful pilot projects in coastal communities based on its guidebook, but recognized that the projects may not have targeted areas most in need of ecological restoration.

“They wanted to know how to prioritize projects so they can identify the best possible adaptations for specific locations in the state,” Herrington said. “We worked with the NJDEP to determine what types of natural and nature-based solutions work best in a given environment, considering factors like the project’s distance from a community, its consistency with the landscapes around it, and whether it would restore what’s there rather than building something new.”

The report notes that in contrast to hard or traditional “gray” engineered structures like seawalls and bulkheads, natural systems can offer equal or better hazard protection, avoid negative impacts to the environment and naturally adapt to changing conditions over time. However, these natural defenses have degraded significantly in New Jersey over the last century due to development, climate change and other trends.

Working with input from coastal experts and stakeholders, the NJDEP and Monmouth researchers set out to develop a project prioritization framework that places green adaptations on par with gray ones for protecting communities and ecosystems. The framework provides a high-level, landscape-scale screening of possible coastal ecological adaptations using geographical information system (GIS) data housed and managed by the NJDEP. The objective is to prioritize those adaptations that address a particular coastal issue of concern, such as coastal inundation, and are aligned with existing and/or future land use and management goals.

For more information on the report, contact Dr. Thomas Herrington at therring@monmouth.edu.

Sept. 14 Panel to Focus on Stormwater Pollution and Local Watersheds

Members of the public are invited to join a free expert panel discussion on how stormwater pollution and flooding affects the health of local water bodies. The event is being hosted by the Whale Pond Brook Watershed Association in partnership with Clean Ocean Action, the Long Branch Green Team, the Monmouth University Urban Coast Institute, and the New Jersey Chapter of the Sierra Club.

Sophie Glovier, municipal policy specialist for the Watershed Institute, will discuss steps residents can take to combat stormwater runoff pollution in their towns.

Dr. Jason Adolf, Monmouth University endowed associate professor in marine science, will share observations from current research on the linkages between rainfall and microbial pollution at surfing beaches near outflow pipes and storm drains in Asbury Park, Deal and Long Branch. He will also share findings from the Coastal Lakes Observing Network (CLONet) project, in which Adolf and Monmouth students are working with citizen scientists to study water quality in Lake Takanassee, Deal Lake, Sunset Lake, Wesley Lake, Sylvan Lake, Lake Como and Spring Lake.

For more information or questions, contact Faith Teitelbaum at faithteitel@gmail.com. Attendees will be provided a link to the webinar upon registering.

Professor Abate Delivers Interviews on Two Recently Published Books

Randall Abate, professor in the Department of Political Science and Sociology, Rechnitz Family/Urban Coast Institute Endowed Chair in Marine and Environmental Law and Policy, and director of the Institute for Global Understanding, was interviewed on two podcasts and one TV program this summer in connection with his two recently published books: “Climate Change and the Voiceless: Protecting Future Generations, Wildlife, and Natural Resources” and “What Can Animal Law Learn From Environmental Law?”

In May, he was interviewed on the “Little Brains, Big Topics” podcast (posted above), hosted by students at the University of Leeds, U.K. The topic of the interview was “Climate Change, Animal Rights, Future Generations, and Factory Farming,” which addressed topics from both of recently published books.

In July, Abate was interviewed on the “People Places Planet” podcast, hosted by the Environmental Law Institute in Washington, D.C. The interview focused on topics related to the second edition of his book, “What Can Animal Law Learn from Environmental Law?,” which was published in July.

Later in July, he was interviewed on the “Law Matters” program on Cambridge TV, hosted by Jenifer Varzaly, a faculty member at Cambridge University. The interview addressed topics from his “Climate Change and the Voiceless” book.

Abate will teach a new course—PS 298—based on his “Climate Change and the Voiceless” book in fall 2020 at Monmouth.

Checking in With … Kelly Hanna

Year/Semester of Graduation & Major

Year/Semester of Graduation & Major

I am technically part of the class of 2019, though I graduated in December rather than May. My major was Marine and Environmental Biology and Policy, and my minor was Public Policy.

How did you work with the Urban Coast Institute?

I worked in the Phytoplankton and Harmful Algal Bloom (PHAB) Lab with Dr. Adolf, and some of our many projects were funded by the UCI. My favorite project, one in which I was a co-leader of, was our surf beach project. We collected and evaluated samples pre- and post-storm events to assess levels of Enterococcus, a bacterium that is known to cause illness, especially for surfers chasing the post-storm swell. I saw it as a direct avenue to public policy ― provide scientific proof that infrastructure was not serving water quality, and maybe a policy initiative could occur ― a win-win for people and wildlife alike. I also presented research at a UCI-sponsored symposium, Climate Change, Coasts, & Communities, in the spring of my senior year. I spoke about how climate change produces more frequent and disastrous storms, and how factory farms along the coasts and amidst the storms provide a plethora of public and environmental health hazards. The symposium provided me with a platform to not only speak about something I am passionate about, but also to network myself with other scientists, lawyers, and environmental advocates.

What’s next?

Next up, I’m headed to the Kline School of Law at Drexel University in Philadelphia. I hope to continue working as an advocate for environmental justice and all of the intersectional issues that go hand in hand with it. Whether I end up working for a government agency, a firm, or a non-profit organization, I will always try to be at the forefront of environmental issues, on land and in the water.

What is your ocean story?

My family took a trip to Puerto Rico when I was 7. We snorkeled around Desecheo Island, and I was in awe the entire time. We saw colorful fish, lively coral ― so much life! A nurse shark swam right under us, and that’s when I knew that the ocean belonged to all of the sharks, all of the fish, all of the coral. On the way into shore, I saw tires and trash, sticking out in a bad way compared to the beauty of everything else. And that’s when I knew the ocean didn’t belong to humans, at all. From that day forward, I dreamed of a future doing whatever I could to make sure the ocean stayed beautiful and in the hands of its rightful owners. Just last week, I was surfing with my dad, and there were dozens of cownose stingrays catching the waves with us. I felt the same awe as the time I saw the nurse shark while snorkeling in Puerto Rico.