Students in Professor Randall Abate’s Ocean and Coastal Law and Policy class recently delivered final presentations on issues they selected to concentrate on throughout the semester. Among them were Michelle Etienne who focused on whether local beach badge fees were consistent with the public trust doctrine, and Samantha Pawlik, who explored how New Jersey’s offshore wind farms will impact marine life. Learn about their findings in the Q&A and presentation slides below.

Presentation Title: “N.J. Beach Access: Do Beach Badges Violate the Public Trust Doctrine?”

Student Researcher: Michelle Etienne

Student Researcher: Michelle Etienne

Year and Major: Senior, Music Industry

View slides (PDF, 1MB)

What is the public trust doctrine and how does it relate to beach badge fees?

The public trust doctrine is the principle that certain natural and cultural resources are preserved for public use, and that the government owns and must protect and maintain these resources for the public’s use. It originates from Roman law, was established in English Common law, and was adopted in the U.S. in state law. In New Jersey, the public trust doctrine applies to tidal waterways and their shores in the state and establishes that citizens have the right to fully utilize these lands and waters for a variety of public activities that must be protected. These public activities include navigation, commerce, fishing, swimming, bathing, sunbathing, and walking along tidal waterways and their shores. At the beach, the land that reaches the mean high waterline (wet sands) is public trust land managed by the state.

The public trust doctrine in New Jersey requires the state and local governments to ensure adequate access to public trust sites (i.e. the wet sands and open water). There must be adequate linear/lateral access, perpendicular access, and visual access to these public trust lands. This is where beach badges play a role. In order to access the dry private sands, and ultimately the public sands, many New Jersey beaches charge a fee. At each vertical and horizontal access point on the beaches, badge checkers await to make sure that beachgoers have paid a fee to access the beach for the day. The question is whether this practice of charging a fee to access private land and ultimately public land is permissible under the public trust doctrine.

Do you believe charging the public to use the beach violates the spirit of the public trust doctrine? Why or why not?

As a Jersey Shore resident, I am accustomed to having to purchase my seasonal beach badge each summer and the concept of beach badges has never seemed odd to me. However, in researching the PTD and the history of beach badges on the Jersey Shore, I believe that this practice violates the PTD.

Beach badges were first introduced by the town of Bradley Beach in 1929 for the sole purpose of limiting beach access to only town residents and visitors in town hotels. But it quickly was recognized as a revenue-generating method and many beach towns followed suit. In 1972, in the landmark case of Borough of Neptune v. Avon-by-the-Sea, Avon-by-the-Sea attempted to charge less for badges for town residents and more for out-of-town residents to access its beaches. The court held that municipalities may not discriminate against nonresidents with badge fees. Although this case established that there may not be any discrimination in pricing, badge fees still restrict some people from being able to go to the beach. These fees also have no limit to how much they can be increased each year. In Avon-by-the-Sea alone, daily badge fees went up by $3 in just two years and a regular adult season badge increased by $10. Although these badge fees are the same for everyone, these fees are becoming more expensive, ultimately making it less affordable for some New Jersians to access the beach. This reality undermines the goals of the public trust doctrine and the duty that state and local governments have to ensure adequate access to public trust lands.

Beach badges were first introduced by the town of Bradley Beach in 1929 for the sole purpose of limiting beach access to only town residents and visitors in town hotels. But it quickly was recognized as a revenue-generating method and many beach towns followed suit. In 1972, in the landmark case of Borough of Neptune v. Avon-by-the-Sea, Avon-by-the-Sea attempted to charge less for badges for town residents and more for out-of-town residents to access its beaches. The court held that municipalities may not discriminate against nonresidents with badge fees. Although this case established that there may not be any discrimination in pricing, badge fees still restrict some people from being able to go to the beach. These fees also have no limit to how much they can be increased each year. In Avon-by-the-Sea alone, daily badge fees went up by $3 in just two years and a regular adult season badge increased by $10. Although these badge fees are the same for everyone, these fees are becoming more expensive, ultimately making it less affordable for some New Jersians to access the beach. This reality undermines the goals of the public trust doctrine and the duty that state and local governments have to ensure adequate access to public trust lands.

What are some ways that the state or municipalities can better uphold the rights granted in the public trust doctrine?

Many shore towns argue that badge fees are necessary to their town budget. The towns reinvest these revenues to help maintain the beaches for public use. While towns need to have adequate funding for beach maintenance, I have two suggestions that I believe would help towns raise adequate funds for beach maintenance while upholding the rights granted in the PTD.

My first suggestion is for the state to establish a percentage limit on the amount a town can increase its badge fees per season. Towns would need permission from the state to increase fees above these levels. This would ensure that towns aren’t increasing these fees too quickly and that they have legitimate, strong reasoning for these increases that are beneficial to the maintenance of public trust lands. My next suggestion is that all beach towns adopt a “Beach Utility,” which is a committee of town elected officials that dedicates all revenue derived from beach badge sales back into the maintenance of the beach. This would ensure that the money made from badge sales is used exclusively to maintain the private and public beach lands.

Presentation Title: “Implementing Safeguards for New Jersey Offshore Wind Projects to Address Impacts to Marine Life”

Student Researcher: Samantha Pawlik

Student Researcher: Samantha Pawlik

Year and Major: Senior, Political Science

View Slides (PDF, 1MB)

Your presentation examined the issue of offshore wind energy off the New Jersey coast. Where does progress on wind development stand in New Jersey today and what are the next steps?

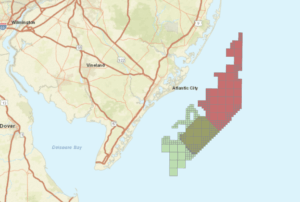

New Jersey is currently approved to start construction of the nation’s largest combined offshore wind farm in 2024. The New Jersey Board of Public Utilities (NJBPU) awarded a combined 2,658 MW of offshore wind capacity to Ørsted’s Ocean Wind II and Shell’s Atlantic Shores Offshore Wind, bringing the state’s total planned capacity to over 3,700 MW. Gov. Phil Murphy signed Executive Order No. 92 in 2020, setting the goal of 7,500 MW of offshore wind by 2035. The federal government, led by the Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM), is responsible for identifying, leasing, and reviewing offshore wind areas and projects located between three and 200 nautical miles from the U.S. coast. BOEM will review and approve the construction and operation phases for the two projects, which includes environmental and technical reviews as well as design and implementation plans.

You discussed some of the risks that offshore wind projects pose to marine life, and cetaceans in particular. Can you describe what you found?

Although there is limited research on this topic, I was able to find enough information to conclude that offshore wind farms do have a significant impact on marine wildlife and their habitat. Excessive noise can affect marine wildlife behavior, particularly those species that are more sensitive to sound, that rely on their use of vocalization for communication, and those that use echolocation for navigation, such as cetaceans. Preconstruction activities of offshore wind farms include use of geosurveys that use high-energy acoustic sources to transmit sound, which creates an image of the seafloor. Construction requires a variety of sound-generating activities, including seismic exploration, excavation with explosives, dredging, ship and/or barge operations, and pile driving. Even during the operations phase of wind turbines, researchers have found that the slight vibrations that travel through the poles cause sound radiation through the seafloor. These activities all result in disturbances to marine habitat and can cause negative impacts to marine wildlife behavior and health.

What are some of the ways those risks could be mitigated on the technology and policy sides?

Mitigating these risks through technology and policy reforms is key to implementing such a large-scale project in a safe manner. Cutting-edge technology has been a crucial component in the construction of offshore wind farms. My project discussed suction bucket and gravity-based foundations, which are new technologies that can be used in place of monopile foundations as a quieter and less disruptive alternative during construction. Collaboration between agencies to provide efficient documentation of progress and findings, transparency of information with shore towns and public education on the projects, and continued research efforts are all key to attenuate the threats posed by offshore wind farms. Duke University recently received a $7.5 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to assess the risks that offshore wind energy development along the East Coast may pose to birds, bats, and marine mammals. This type of research will help inform decisions and identify steps that can be taken to reduce harmful impacts on marine wildlife as offshore wind deployment increases.

Mitigating these risks through technology and policy reforms is key to implementing such a large-scale project in a safe manner. Cutting-edge technology has been a crucial component in the construction of offshore wind farms. My project discussed suction bucket and gravity-based foundations, which are new technologies that can be used in place of monopile foundations as a quieter and less disruptive alternative during construction. Collaboration between agencies to provide efficient documentation of progress and findings, transparency of information with shore towns and public education on the projects, and continued research efforts are all key to attenuate the threats posed by offshore wind farms. Duke University recently received a $7.5 million grant from the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) to assess the risks that offshore wind energy development along the East Coast may pose to birds, bats, and marine mammals. This type of research will help inform decisions and identify steps that can be taken to reduce harmful impacts on marine wildlife as offshore wind deployment increases.