It was the winter of 1777-78 and Gen. George Washington was determined to prevent a critical hour for the Revolution from becoming all the more perilous. The British had just taken Philadelphia and with it control of the lower Delaware River and its maritime supply routes. Now Washington worried the British Navy would seize the modest fleet of merchant ships that had been converted to serve the Continental cause. From his headquarters in Valley Forge, he ordered the ships to be hidden in the creeks that fed the Delaware or destroyed rather than risk them being turned against his army.

“We can reap no advantage from keeping the Gallies, cannon and stores in such an exposed situation; and if they should fall into the hands of the enemy, which they would in all probability do; the gallies would be useful to them, and the cannon and stores would be no inconsiderable loss to us,” Washington wrote to the Pennsylvania Navy, a forerunner of America’s own.

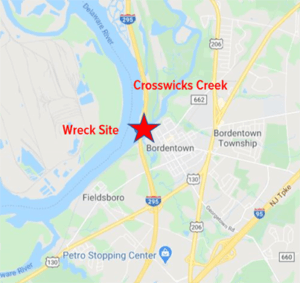

According to historical documents, dozens of vessels were destroyed by the Continentals and the Redcoats during those months in the vicinity of Crosswicks Creek, located 20 miles north of Philadelphia in modern day Bordentown and Hamilton. When the French entered the war in the spring, the British hurriedly evacuated Philadelphia to bolster the defenses of vulnerable New York City. Washington’s troops took advantage of the moment to pull up many of the wrecks and rebuild them for service. But not all.

In the 200 years that followed, small sections of one of those wrecks remained visible in Crosswicks Creek during low tides. However, its remains continued to sink in the mud and erode from the elements, and no signs of it had been recorded since the area was surveyed for highway and bridge projects in the 1980s. But the lost wreck has now been found, thanks to the efforts of Jaclyn Urmey, a Monmouth University master’s degree candidate in anthropology.

The search for the historic vessel took on special significance for Urmey, a Naval veteran and social worker at Joint Air Force Base McGuire-Dix-Lakehurst. When Urmey returned to school in 2018 on her GI Bill, she took a marine archaeology course taught jointly by School of Humanities and Social Sciences Associate Dean Richard Veit and Urban Coast Institute Marine Scientist Jim Nickels.

“When I took that class, I fell in love with it and said, that’s what I want to do,” she said. “I never really considered it as a field of study for me before.”

Locating the Wreck

For her thesis, Urmey interviewed regional historians and pored over historical accounts from civilians living in the area and soldiers who fought on both sides of the war in an attempt to learn more about the vessel. Urmey, Veit and Nickels conducted trips to the creek in November and February to map and photograph the bottom aboard boats owned by the University. The UCI has provided funding as well as equipment, vessel and technical support for the project. In the February trip, Stockton University Marine Science Adjunct Professor Steve Nagiewicz joined the crew with additional technology that helped survey the area.

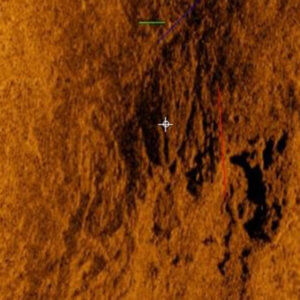

The wreck is located in an area where Crosswicks Creek meets a smaller tributary called Thorton Creek. Side scan sonar imagery (right) shows what appears to be frame timbers from the hull of the approximately 42-foot vessel protruding from a sandbar area in the creek. Urmey estimates only 15% of the ship is still intact.

Based on the wreck’s position close to where the creek meets the Delaware River and signs of charcoal that were discovered in its remains, Urmey believes it was deliberately burned. She said the vessel may have been carrying supplies and fleeing from the British during a two-day raid in May of 1778, ran aground on the sandbar, and was destroyed in place by the British before the Colonials had a chance to hide it.

Urmey’s report also includes information about a second, better-documented wreck located 1,000 feet upstream. Historical records and evidence at the scene indicate the vessel was an approximately 67-foot merchant ship, built for ocean service, that was hidden in the area and sunk by the British during the same raid. She estimated the wreck to be about 60% intact.

Major Philemon Dickinson sent a dispatch to Washington describing the invasion soon after. “With five armed Vessells [sic], & between twenty and thirty flat bottom’d Boats – [British forces] landed at Bordentown & burnt two of Mr Bordens Houses, the two Frigates, & a great Number of other Vessells that were lodged in the different Creeks.”

Another source indicated that upon the British approaching, “two Continental galleys lying near the town [Bordentown] were moved up Crosswicks Creek about a half-mile and an attempt made to conceal them in Bard’s (Barges) Creek. One of them was towed up the creek, but the other grounded near its mouth thus revealing their presence. The enemy sent several armed boats up and boarded and burnt them.”

Veit, Urmey and Nickels would like to return to the site during an extreme low tide to see if the wrecks are still visible by eye and conduct drone work.

“One of the nice things about Jacky’s thesis is that it’s bringing this story to light,” Veit said. “It’s a different aspect of the Revolution. You think of Trenton and Princeton and all the terrestrial battles, but there’s a huge naval component to it. It speaks to the Unites States as a young nation trying to build some naval capability in the face of Great Britain, which had the largest and most accomplished Navy on the planet.”