By Courtney Gosse

Introduction

The Institute for Global Understanding (IGU) co-hosted a film discussion based on Ravi Kumar’s 2014 film, Bhopal: A Prayer for Rain, as part of the 2020-2021 World Cinema Series on January 26 at 7:30 p.m. This event was moderated by Dr. Thomas Pearson, Professor in the Department of History and Anthropology. The faculty discussants for this film were Dr. Datta Naik, Professor of Chemistry, and Dr. Marina Vujnovic, Associate Professor of Communication a nd a specialist in global communications.

nd a specialist in global communications.

The film was released on the 30th anniversary of the Union Carbide disaster, which occurred December 2-3, 1984 in Bhopal, India. The film analyzes the causes of the chemical leak and vapor spread that killed as many as 10,000 people in Bhopal, along with Union Carbide corporate leadership’s responsibility, its local operatives in Bhopal, and local officials’ complicity in creating the conditions that led to the environmental catastrophe, their efforts to avoid accountability, and the disaster’s legacy. The film allows viewers to adequately examine the interdependence among human communities and the natural world; if one side of the relationship is affected, both sides then become affected. As disasters continue to persist today, due to climate change and human errors, there are many lessons that can be learned from analyzing what is considered the world’s worst industrial disaster: the catastrophe of Bhopal.

Information About the Film

The director, Ravi Kumar, is a famous Bollywood actor and director. He was inspired to make the film as early as 2004 after reading Sunjoy Hazarika’s Bhopal, the lessons of a tragedy. He discovered that few members of the younger generations knew about the Bhopal disaster, which fascinated him, and pushed him to believe that this was a film that needed to be made.

In 2010, unfortunately, Kumar ran into the problem of getting the film released. His efforts to release the film were plagued by controversy as the Dow Chemical company, which acquired what had been Union Carbide in 2001, blocked efforts to screen the film. Local activists in Bhopal also had real concerns about the film’s message. However, this did not stop Kumar from completing the film’s production. Next, when the film was considered complete, Kumar then faced another problem: getting a distributor to finance the film’s release. A film in which thousands of people died in the most horrible ways would prove to be a difficult endeavor in this regard. Kumar eventually managed, with the help of actor Martin Sheen, to screen the film at a few different international film festivals. As a result of these events, the film began attracting a larger audience, which simply provided more attention to the Bhopal tragedy. Therefore, Kumar decided to show the film on the 30th anniversary of the event with a premiere in Bhopal.

Discussion with Dr. Datta Naik about Toxicity

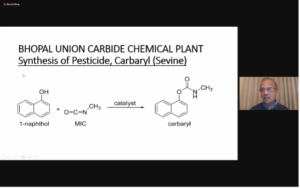

Dr. Naik provided viewers with an explanation of what happened logistically regarding the Union Carbide product’s toxicity and why it had killed so many people in Bhopal in 1984. To begin, Union Carbide was making and selling a toxic pesticide, Sevine, made from MIC (methyl isocyanate), which was made at the plant, and 1-naphthol, which was outsourced from another location. The chemical compound MIC is extremely toxic; the threshold limit value set by the American Conference on Government Industrial Hygienists is 0.02 parts per million (ppm). Although the MIC’s odor cannot be detected at 5 ppm by most people, its potent lachrymal properties provide an excellent warning of its presence. (At 2-4 ppm, subjects’ eyes are irritated, the first sign of exposure.)

Dr. Naik provided viewers with an explanation of what happened logistically regarding the Union Carbide product’s toxicity and why it had killed so many people in Bhopal in 1984. To begin, Union Carbide was making and selling a toxic pesticide, Sevine, made from MIC (methyl isocyanate), which was made at the plant, and 1-naphthol, which was outsourced from another location. The chemical compound MIC is extremely toxic; the threshold limit value set by the American Conference on Government Industrial Hygienists is 0.02 parts per million (ppm). Although the MIC’s odor cannot be detected at 5 ppm by most people, its potent lachrymal properties provide an excellent warning of its presence. (At 2-4 ppm, subjects’ eyes are irritated, the first sign of exposure.)

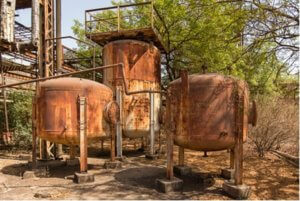

Next, MIC was created in large quantities at the Union Carbide plant and needed to be kept cool (near the freezing point) when not in use, which was the case in Bhopal. The chemical was then kept in large 60-ton tanks while waiting to be utilized properly. The chemical leak started from these storage tanks due to lack of specific protocols being followed, as well as the event itself, which was the MIC reacting with other chemicals and escaping into the atmosphere. Several protocols were not followed: (1) the tank’s refrigeration was off, (2) one out of the three tanks was empty, and (3) the other two tanks

Next, MIC was created in large quantities at the Union Carbide plant and needed to be kept cool (near the freezing point) when not in use, which was the case in Bhopal. The chemical was then kept in large 60-ton tanks while waiting to be utilized properly. The chemical leak started from these storage tanks due to lack of specific protocols being followed, as well as the event itself, which was the MIC reacting with other chemicals and escaping into the atmosphere. Several protocols were not followed: (1) the tank’s refrigeration was off, (2) one out of the three tanks was empty, and (3) the other two tanks  were filled more than halfway (~30 tons of MIC). The chemical reaction that took place was due to an operation error during the rinsing of the vent pipes; water flowed into the MIC storage tank, which is when everything started to go wrong. An exothermic reaction between MIC and water occurred, producing intense heat in the tank’s confined space. The temperature and pressure started to rise, which caused part of the MIC distillates to decompose and to generate hydrogen chloride gas. This gas formed hydrochloric acid with water (another exothermic reaction) and corroded the stainless-steel tank, dissolving it into iron. The dissolved iron, acting as a catalyst, caused a trimerization reaction to produce trimethyl isocyanate (a solid). This trimerization reaction did not go into the atmosphere, but rather was exothermic and produced extreme heat, which simply increased the temperature and pressure in the tank, reaching 250 °C (482 °F), causing the tanks to rupture. Eventually, the toxic MIC gas along with several other toxic gases, all heavier than air, leaked out of the tank and into the plant, and then finally into the low atmosphere of Bhopal.

were filled more than halfway (~30 tons of MIC). The chemical reaction that took place was due to an operation error during the rinsing of the vent pipes; water flowed into the MIC storage tank, which is when everything started to go wrong. An exothermic reaction between MIC and water occurred, producing intense heat in the tank’s confined space. The temperature and pressure started to rise, which caused part of the MIC distillates to decompose and to generate hydrogen chloride gas. This gas formed hydrochloric acid with water (another exothermic reaction) and corroded the stainless-steel tank, dissolving it into iron. The dissolved iron, acting as a catalyst, caused a trimerization reaction to produce trimethyl isocyanate (a solid). This trimerization reaction did not go into the atmosphere, but rather was exothermic and produced extreme heat, which simply increased the temperature and pressure in the tank, reaching 250 °C (482 °F), causing the tanks to rupture. Eventually, the toxic MIC gas along with several other toxic gases, all heavier than air, leaked out of the tank and into the plant, and then finally into the low atmosphere of Bhopal.

Lastly, due to misinformation and lack of education regarding the chemicals being held and produced at Union Carbide, essential workers, staff members, and even the local community knew nothing about how to treat the symptoms that were present during the gas leak. Also, Union Carbide had not conducted emergency drill or training prior to the incident, which is unfortunate because all that needed to be done to escape the inhalation of the toxic gas was to run to higher ground. Therefore, due to lack of education and training, thousands of people were then greatly affected by this horrific event. In fact, the official immediate death toll was 2,259. Then, in 1991, after being reassessed, the total count was 3,928 deaths. However, unofficial total deaths are estimated to be around 14,410. Also, the amount of people injured during this event is estimated to be 574,000. To put this into perspective, Bhopal’s population in 1984 was 850,00; therefore, over half of the population was affected. Overall, there were many potential efforts that could have prevented this disaster.

Lastly, due to misinformation and lack of education regarding the chemicals being held and produced at Union Carbide, essential workers, staff members, and even the local community knew nothing about how to treat the symptoms that were present during the gas leak. Also, Union Carbide had not conducted emergency drill or training prior to the incident, which is unfortunate because all that needed to be done to escape the inhalation of the toxic gas was to run to higher ground. Therefore, due to lack of education and training, thousands of people were then greatly affected by this horrific event. In fact, the official immediate death toll was 2,259. Then, in 1991, after being reassessed, the total count was 3,928 deaths. However, unofficial total deaths are estimated to be around 14,410. Also, the amount of people injured during this event is estimated to be 574,000. To put this into perspective, Bhopal’s population in 1984 was 850,00; therefore, over half of the population was affected. Overall, there were many potential efforts that could have prevented this disaster.

Discussion with Dr. Vujnovic on Corporate Social Responsibility

Dr. Vujnovic helped viewers better understand Union Carbide’s failure to exercise responsibility (now called Dow Chemical Company) for this event that occurred more than three decades ago. She also explained how the attitude portrayed toward this disaster, along with the lack of a coordinated response, shows exactly how not to do crisis management: “delayed, denied, and deflected.” The story of Bhopal is simply about collusion between governments (both Indian and American), along with large corporate powers. The groups involved continue to obstruct justice for the Bhopal disaster’s victims due to lack of enforcement regarding liability. For example, even today, the company continues to refuse to provide basic information regarding the disaster to reporters, constantly giving excuses and blaming the local government as well as the Bhopal community for the crisis. However, legal documentation indicates that everything is traced back to Warren Anderson, the former CEO of Union Carbide. Anderson had signed the paperwork knowing that there would be safety issues at the Bhopal location simply for the purpose of cost-saving measures. The documents eventually surfaced in 1981 proving this, along with the number of employees hired and fired, as well as the lack of safety training protocols throughout the company’s locations.

Dr. Vujnovic helped viewers better understand Union Carbide’s failure to exercise responsibility (now called Dow Chemical Company) for this event that occurred more than three decades ago. She also explained how the attitude portrayed toward this disaster, along with the lack of a coordinated response, shows exactly how not to do crisis management: “delayed, denied, and deflected.” The story of Bhopal is simply about collusion between governments (both Indian and American), along with large corporate powers. The groups involved continue to obstruct justice for the Bhopal disaster’s victims due to lack of enforcement regarding liability. For example, even today, the company continues to refuse to provide basic information regarding the disaster to reporters, constantly giving excuses and blaming the local government as well as the Bhopal community for the crisis. However, legal documentation indicates that everything is traced back to Warren Anderson, the former CEO of Union Carbide. Anderson had signed the paperwork knowing that there would be safety issues at the Bhopal location simply for the purpose of cost-saving measures. The documents eventually surfaced in 1981 proving this, along with the number of employees hired and fired, as well as the lack of safety training protocols throughout the company’s locations.

Another example of corruption is the settlement to which Union Carbide agreed with the U.S. and Indian governments. The company agreed to this settlement to save its image and reputation, but the money was given to the Indian government to provide each victim and family with proper compensation (around $1,000 per victim). However, the Indian government enacted the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster Act in 1985, which enabled the government to act as a legal representative for the victims. Therefore, once this money was paid, the Indian government did not give all the money to the victims and instead kept most of the estimated $370 million in its own coffers. The victims and their families continue to campaign in the hope that they will one day receive proper compensation for the disaster.

Another example of corruption is the settlement to which Union Carbide agreed with the U.S. and Indian governments. The company agreed to this settlement to save its image and reputation, but the money was given to the Indian government to provide each victim and family with proper compensation (around $1,000 per victim). However, the Indian government enacted the Bhopal Gas Leak Disaster Act in 1985, which enabled the government to act as a legal representative for the victims. Therefore, once this money was paid, the Indian government did not give all the money to the victims and instead kept most of the estimated $370 million in its own coffers. The victims and their families continue to campaign in the hope that they will one day receive proper compensation for the disaster.

On a more positive note, although there was a lack of global support and attention given to the Bhopal disaster, a nonprofit organization, the Chingari Trust, continues to help combat the disaster’s effects on the local community. Founded by survivors Rashida Bee and Champadevi Shukla in 2006, the organization provides economic and livelihood support programs primarily to women and children in the affected area.

On a more positive note, although there was a lack of global support and attention given to the Bhopal disaster, a nonprofit organization, the Chingari Trust, continues to help combat the disaster’s effects on the local community. Founded by survivors Rashida Bee and Champadevi Shukla in 2006, the organization provides economic and livelihood support programs primarily to women and children in the affected area.

Overall, what can be taken from this film and the event that it depicts is that there is absolutely no justice without proper accountability. Multinational corporations, like Union Carbide, always seem to be in the race for the bottom line, yet, where are the ethics in this approach? It seems that the bottom line is always put first, before human decency or proper respect for human rights. The U.S. approach to conducting international business must change. It cannot be about what is allowable; it needs to be about what is a proper and safe way of conducting business (i.e., protecting people and protecting the environment). Although the role of governments is important in these situations, the ultimate responsibility lies with the corporations themselves. It is simple: Do not take advantage of vulnerable communities and adopt ethical practices in your work.