Women, Cars, and Liberation

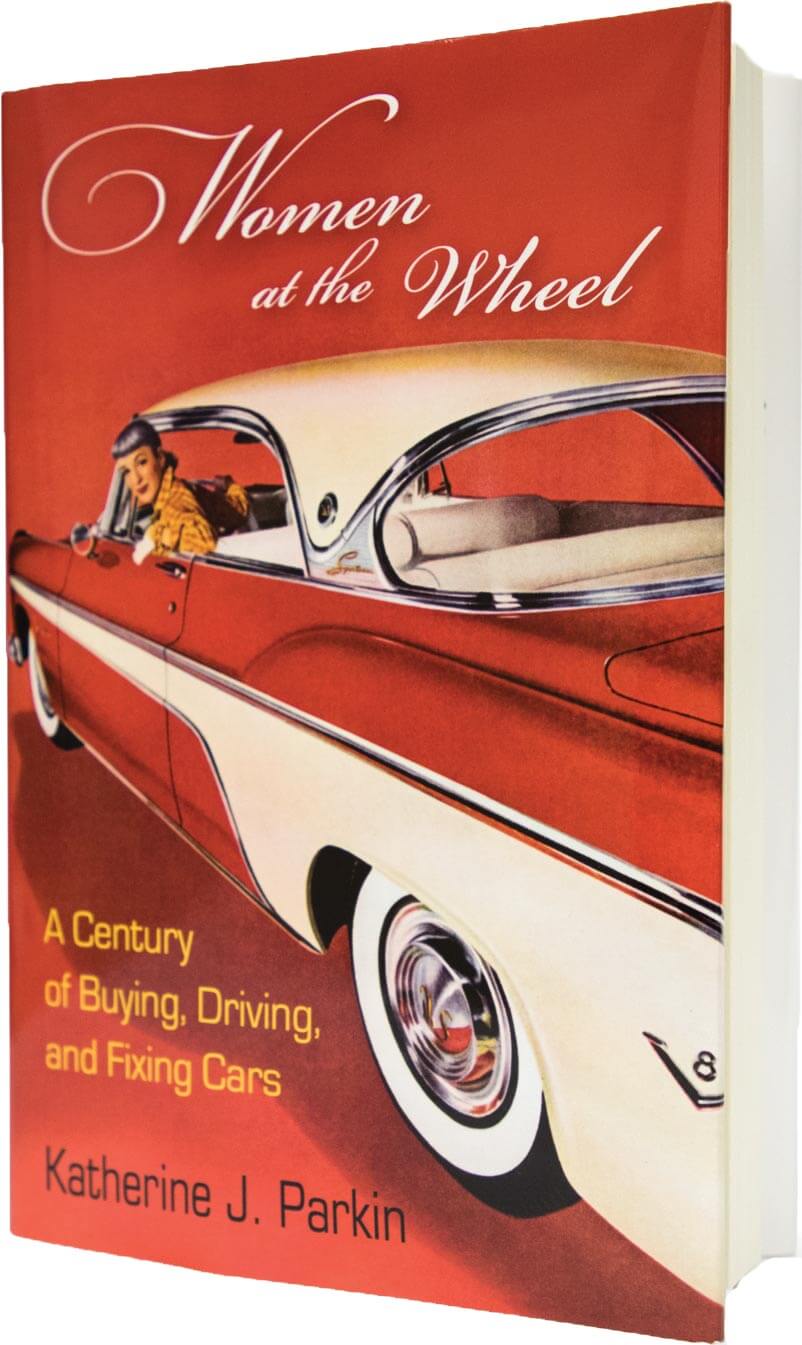

An annotated conversation with Katherine J. Parkin, author of the new book ”Women at the Wheel: A Century of Buying, Driving, and Fixing Cars.”

In Women at the Wheel: A Century of Buying, Driving, and Fixing Cars, History Professor Katherine J. Parkin examines the fascinating history of how American car culture and American attitudes toward gender have overlapped, conflicted, and defied expectations.

Parkin takes readers from the days when gasoline-, electric-, and steam-powered vehicles vied for supremacy through to the present, examining everything from NASCAR driver Danica Patrick’s advertising work[1] to Volkswagen’s relaunch of the Beetle, with the tagline “It’s a boy.”

Along the way, she shares insights on the (occasionally bizarre) automotive subcultures she unearthed during her research and chronicles decades of cringe-worthy automotive advertising campaigns.

What drew you to the topic of women’s relationships with cars over the years?

When I was working on my last book[2], I came across a statistic that 50 percent of driver’s license holders are women. I clipped that out and put it on my wall to think about. At first, I thought that maybe the women’s movement was a liberating force that encouraged women to drive. But I found that wasn’t the case; the growing number of women drivers was part of a trend. The number of women drivers grew across the 20th century, and women now outnumber men.[3] I don’t think it was really about liberation so much as that society really needed women to drive and women clearly sought it out.

You write about a number of very particular subcultures, including grandmothers who work as mechanics. Where did you first encounter them?

I grew up watching David Letterman, so I’d see him having [auto mechanic and cable host] Lucille Treganowan[4] on. She was a grandmother in the 1980s, but the grandmother-mechanic figures that I discovered did not start out working as grandmothers. They only became acceptable as mechanics because as they aged, they were considered to be asexual. We don’t consider older women to be sexual beings. I think there’s a way in which we allow women to be engaged with a car—as long as they’re not a threat to men’s masculinity.

Does that also apply to the car-repairing nuns you wrote about?

Yes. A nun, whose nickname was Sister Fixit[5], taught high school women how to fix their cars and talked to men about God while she worked under the hood, but it was all seen as holy work. It’s not seen as anything untoward.

You discussed the arrival of women-owned garages in the second half of the 20th century. Do you find that they’re still vital today, or was that more of an isolated moment in history?

Auto repair garages persist in being male-dominated, but there have always been exceptions. There’s a wonderful garage in Philadelphia that just won an award for the best garage in the city[6], and it’s owned and operated by a woman who works in her trademark red heels. They opened it with a beauty bar attached to it, so you bring in your car for repairs and you get your nails or hair done at the same time. They even advertised mixing your own nail polish paint, which is a parallel for mixing your paint for your car. It’s trying to make dealing with your car more accessible to women—an effort that has been fairly consistent throughout history.

One of the most interesting parts of the book was your research into the time before gas-powered cars were ubiquitous.

I think it’s important to recognize how much everything was in play. We tend to think only of gas or electric cars, but there was a third, steam, and although it didn’t survive it was certainly a contender. The woman who was the first to drive in Washington, D.C., drove a steam car.[7] Her dad was a doctor, and she was his driver; she would help him go around to his patients. Steam was even more complicated than gas and electric, and tended to be more popular in urban areas with short distances and a guarantee of finding water. Women have long been identified with electric cars in the popular imagination, but they drove steam and gasoline-powered cars, too.

You discuss how early electric cars were often marketed toward women. Is it significant, then, that today’s high-profile manufacturer of electric cars, Tesla, is named after a man?

When I was finishing up my book, Tesla had just emerged as a strong contender in the car industry. Car companies have long placed an emphasis on science and on inventors—we admire Ford, we admire these men who created these cars. However, we also know that American car companies have long sought to crush electric cars. It is no surprise that it took a Japanese automaker, Toyota, to break into the American market with the first successful hybrid, the Prius.

I think that they appeal a lot to women, but most automakers don’t believe being successful with women is good. Take for example the popularity of the revitalized Volkswagen Bug. After recognizing their success, the company rejected women and said to themselves, “Okay, we’ve sold it to all these women; now let’s change it into a boy!”[8] They brought in Porsche designers to masculinize the rounded beetle shape and removed the flower vases. It’s a very contradictory impulse.

Were there any sections of the book that were particularly challenging to write?

One of the most difficult parts was writing about police and sexual violence. I found that police used their power to coerce sexual acts from women they pulled over. Similar experiences were found with driving instructors and their assaults—I think it’s an unspoken experience that women are having, that there’s a risk when you’re getting into a car with a male stranger.

We have a notion that cars represent freedom, but women are constantly told to be afraid with their car: Don’t pump your own gas; it’s dangerous. Parking garages are dangerous. I find that the fears are not substantiated in the crime statistics, but also that we don’t hear much about women’s experiences. That’s partly what motivated me to write the book. Women are having different experiences with cars and we don’t know it. In the case of the crimes that are occurring, the silence means no laws or policies are being developed to help police the perpetrators.

Women worked with cars in both world wars. Did one war have more of an impact as far as changing perceptions of gender and automobiles?

In some ways, I think the First World War had more revolutionary potential. The American suffragist Rosalie Jones said, effectively, “We have suffrage, now we need to learn how to fix a car.” It was part of this understanding of women’s independence, the idea that women would find independence in their relationship with a car, in learning how to drive and assisting, as Gertrude Stein did overseas, transporting goods and being a part of the war effort.

I have less of a sense of that from the Second World War. Certainly, more women were involved, more women drove, more women were mechanics.[9] But I didn’t find anyone from World War II saying, “This is really going to open doors for women; this is really going to transform their lives.”

One of the most memorable images you bring up in the book is this moment where male car designers attempted to understand a woman’s driving experience by wearing fake nails and approximating wearing a dress. Is automotive design still an overwhelmingly male field?

Not only is automotive design still overwhelmingly male, it is also consistently tone deaf to the American consumer. The example you mentioned, of men wearing trash bags for dresses and taping paper clips to their fingers, was proudly detailed in press releases. Companies proudly proclaim that they’re working hard to understand women. I found it shocking that they would believe that would be a positive thing today. It really only reveals how few women are involved.[10]

If you look at Volvo, which is a very successful car in appealing to women and safety, they put together a team to create a pink, prototype Dodge La Femme kind of car. Why wouldn’t they put them to work to make a car that was good and appealed to everyone? I found that disheartening. Volvo proudly touted that they created floor mats that you could change out with the seasons. Listening to consumers, particularly women, seems like a pretty low bar that the car industry still can’t cross.

Was there anything you found that surprised you, or defied expectations of what you were looking for?

I structured the book along the lines of a woman’s experience with a car: you learn to drive, you get your license, you buy your car, you care for your car. What I didn’t expect to find in my research were all the ways people identified with the car. People’s relationships with their cars didn’t really fit into expected patterns that I had anticipated, to the extent that people named their cars, had sex in their cars—or with their cars.[11]

Once when I was teaching, I was talking about the notion of women assaulting the car as a way of getting back at a betrayal by a man. One of my students said, “Oh yeah, I did that. I got in trouble.” As I was finishing writing the book, Beyoncé’s Lemonade came out, and she’s mad at Jay-Z’s infidelity and beating cars with a baseball bat.[12]

Do you consider yourself a car person, or did writing this book turn you into one?

I’ve always enjoyed driving, and like the independence it gave me. I’ve driven in Europe; I’ve driven stick in England on the other side of the road. But I’m not a car person. I don’t know much of anything about under the hood. Writing this book made me more aware of the ways that cars permeate the American experience. If you take something like music, the Beatles have very few songs that reference the car, but American musicians use the car to talk about escaping bad relationships (Tracy Chapman, Melissa Etheridge), avenging bad behavior (Carrie Underwood, Beyoncé), seeking out freedom and joy in cars.

Footnotes

- According to TiVo, Patrick’s “Enhancement” commercial for GoDaddy.com was the most watched commercial during the 2009 Super Bowl.

- Food Is Love: Advertising and Gender Roles in Modern America. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2006.

- According to the most recent statistics from the Federal Highway Administration, there are 1,365,947 more female than male licensed drivers in the U.S.

- Treganowan also appeared as herself in a 1996 episode of “Tool Time,” the show-within-a-show on the Tim Allen vehicle Home Improvement.

- Sister Joan Marese. She also did carpentry, plumbing, and electrical work, according to a 1973 UPI news article.

- Girls Auto Clinic, in Upper Darby, Pa., was named Philadelphia magazine’s “Best Multipurpose Garage” in 2017.

- Anne Rainsford French. She was nicknamed “Miss Locomobile” by some D.C. residents, according to a 1952 Life magazine article.

- VW’s 1959 “Think Big” campaign for the Beetle was named the top advertising campaign of the 20th century by Ad Age.

- Among them was Princess Elizabeth, later Queen Elizabeth II.

- In 2011, General Motors named Mary Barra senior vice president of global product development. Three years later she was appointed CEO, becoming the first woman to lead a major automaker.

- According to Wikipedia, “Mechanophilia (or mechaphilia) is a paraphilia involving a sexual attraction to machines such as bicycles, motor vehicles, helicopters, ships, and aeroplanes.”

- Five years before Beyoncé went Angela Bassett on a row of cars for her music video, Jay-Z and Kanye West destroyed a $350,000 Maybach in the video for their song “Otis.” The rappers later auctioned the car off for charity.