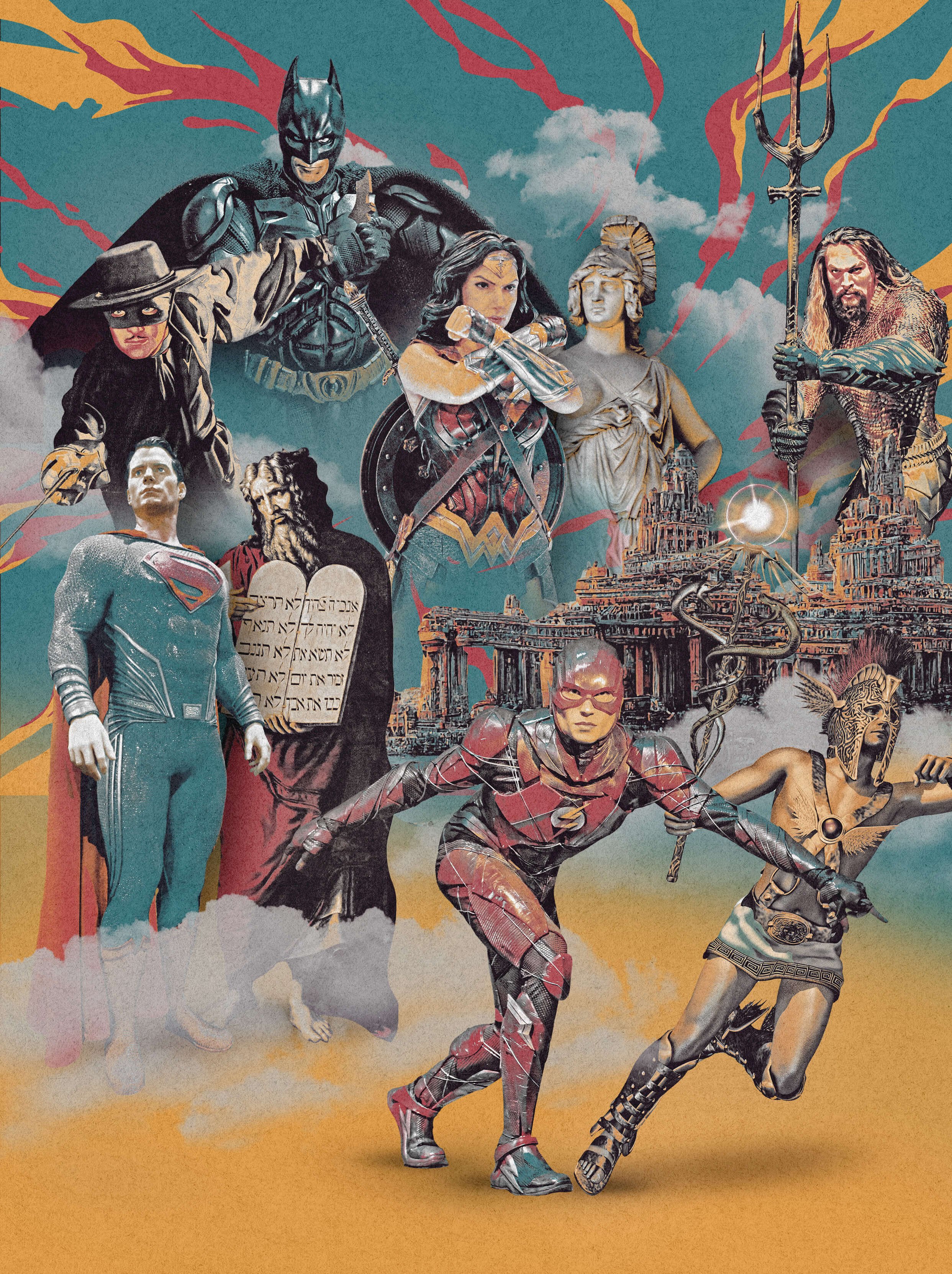

Where Comics Meet Classics

Inside a course that explores the literary origins of DC Comics’ Justice League characters.

Many of the students who take Associate Professor of English Stanley Blair’s general education course The Literary Origins of the DC Justice League are already familiar with the comic book characters they discuss. But while the students might know about contemporary superheroes on film and TV, few know about the literary origins of those heroes—not how the characters became superheroes, but how their creators came up with them.

“The question that I ask students at the beginning of the course and that guides their research is this: ‘Everyone knows that the film and TV superheroes come from earlier comic book superheroes, but where did the comic book superheroes come from?’” says Blair. “The answer,” he says, “is a combination of classical literature, popular pulp fiction of the early 20th century, and film.”

During the semester, Blair’s students read excerpts from works by Homer, Plato, Sir Thomas Malory (of King Arthur fame), Edgar Allan Poe, and others. One of the discussions that is often eye-opening for students is when Blair reviews each character’s first comic book appearance.

“We end by analyzing elements of the first page of the superhero’s first comic book appearance in terms of where their characteristics come from in classical literature, popular literature, and film,” says Blair. “By the end of that exercise, students are amazed that they can read this old comic book critically in terms of specific source influences, something most readers can’t do.”

Blair created the course, which is open to students from all majors, because he believes the study of literature enriches one’s general knowledge and enables individuals to gain a critical perspective on their own experiences.

Case in point: One of Blair’s students, senior accounting major Zach Francese, went to Six Flags to ride the Superman: Ride of Steel roller coaster. While waiting in line, Francese began telling his girlfriend about something that had recently been discussed in class: Superman’s origin on the planet Krypton and his being sent to Earth as paralleling the birth and infancy of Moses in the book of Exodus.

“Superman’s creators were Jewish,” says Blair, “so it’s reasonable to infer that Moses would have had an influence on their development of the character.”

Blair said that Francese made a further connection to the class when he explained that the formulation of Superman’s Kryptonian name, Kal-El, paralleled other biblical names like Gabri-el and Micha-el, with the “El” signifying “god” in ancient Hebrew.

“Critical thinking is something we try to foster throughout the general education curriculum,” says Blair. “When students bring up reading assignments while waiting in line for a roller coaster, that suggests a way of thinking critically about, and observing critically, the culture in which we live.”

Though Blair himself was a fan of Marvel Comics growing up, he thought that the DC Comics made for a better literature course. Many of the Marvel characters that students know about nowadays emerged after World War II and involved exposure to some form of radiation.

“That might be the gamma radiation that causes Bruce Banner to turn into the Hulk or Peter Parker getting bitten by a radioactive spider,” says Blair. “In that sense, those kinds of superheroes are an American response to the age of atomic weapons.”

DC superheroes such as Superman, Batman, and Wonder Woman, on the other hand, were created before the U.S. entered World War II and have a variety of other scientific explanations for their origins as superheroes. Therefore, they’re a little easier for non-English majors to connect to classical literature in a general education literature requirement course.

“For example,” says Blair, “Superman’s superpowers on Earth have to do with science-based explanations like different planets’ gravities and atmospheres, as also depicted in Edgar Rice Burroughs’ 1917 novel A Princess of Mars.”

However, thanks to the popularity of his Literary Origins of the DC Justice League course, Blair is looking to expand the number of figures that are in it and include some Marvel characters—even some villains. His eventual goal is to develop his comic book course offerings into a textbook.

Did You Know?

Batman’s Beginnings

In the first installment of the Warner Bros. Batman film franchise in 1989, a mugger asks the caped crusader, “Who are you?,” to which actor Michael Keaton’s character replies, “I’m Batman.”

While most fans know Batman’s origin story as being a creation of billionaire Bruce Wayne as vengeance on the criminals who killed his parents, few might realize that the character itself is woven from two disparate threads.

One of those is Zorro, whose alter ego is Don Diego Vega, the richest landowner in Spanish colonial Alta California. Zorro is a masked vigilante who vows to “avenge the helpless, to punish cruel politicians, to aid the oppressed”—not unlike Batman. In fact, many Batman films and TV shows often have a Zorro reference, such as the movie that’s playing in the theater the night that Bruce Wayne’s parents are murdered.

Batman’s creators were influenced by the 1920 silent film The Mark of Zorro, which in turn was based on a novel published one year earlier by Johnston McCauley.

The other source for Batman’s character is The Shadow, who appeared on radio and in pulp fiction and films. The Shadow has an alter ego too: Lamont Cranston, a wealthy “man-about-town” who gets driven around in limousines. In the 1937 film The Shadow Strikes, Cranston also has a personal assistant with a British accent named Henry Hendricks—a possible inspiration for Bruce Wayne’s butler, Alfred.