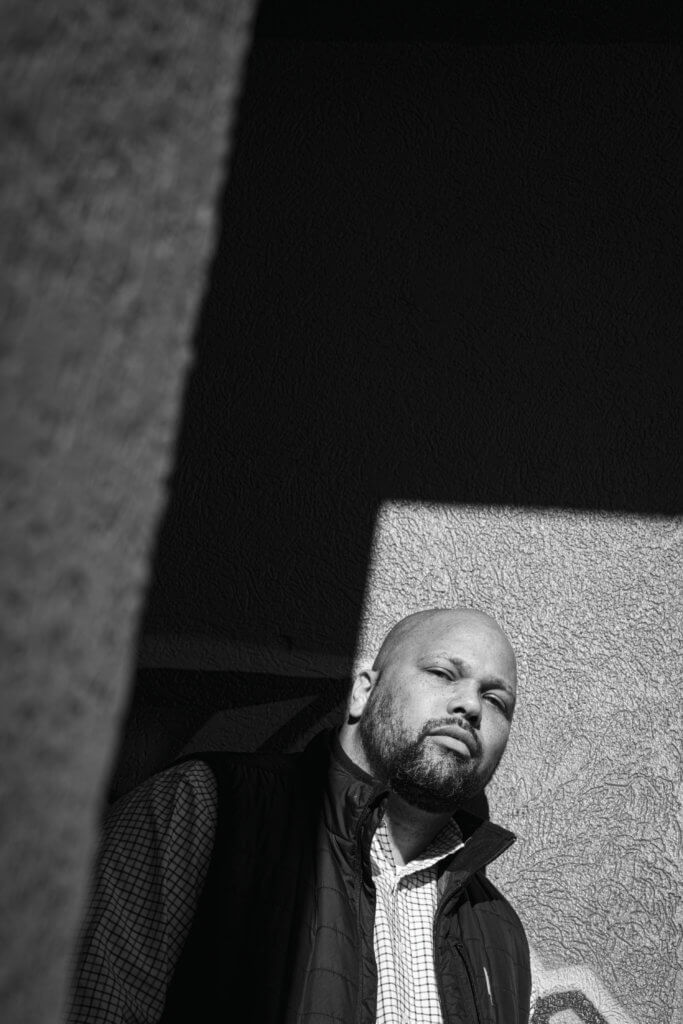

The Resilient One

It’s often challenging to identify definitive turning points in the path of someone’s life. But Damon Colbert ’15, ’16M, ’20Ed.D. doesn’t hesitate when asked to recall the exact moment his life took a turn toward trouble. It was the end of his first marking period at Long Branch High School, and for the first time in his life Colbert had taken pride in his grades, which was no small feat.

Colbert’s childhood had been mired in disadvantages and obstructions. His father was an emotionally and physically abusive addict who maintained only the faintest pretense of parenting, leaving Colbert’s mother to care for her son and three daughters while wrestling with her own substance abuse.

“Growing up, we really had nothing,” says Colbert. “We were dirt poor. My father was running around in the streets, neglecting his family, so I had no guidance, no role models or inspirations or anyone giving me a sense of positive manly direction or support. My mother was struggling with her own demons and spent most of her attention on my sisters. So, I was kind of left to figure it out for myself.”

In middle school this proved extremely difficult. Colbert’s grades were awful, his behavior abysmal, and he generally classifies that time as “just barely getting by.” But he vowed to begin high school with renewed focus and tenacity. He started playing football and actually tried to apply himself academically. When he got his first report card, Colbert was elated to see his efforts had paid off.

“I had B’s and C’s, maybe even an A in there, but for the first time no D’s or F’s. I was extremely excited,” says Colbert. “I was even more excited to show my father, because he was always hard on me, and I would get a beating for bad grades. He beat me with a belt or extension cord until I was in eighth grade. And when I finally showed him my report card, he shrugged and said, ‘Huh. You got C’s. This isn’t nothing.’”

Here Colbert pauses and sighs.

“I really wanted him to be proud of me, but it wasn’t impressive enough to him,” he continues. “That was a turning point in my life. I came to him with good grades expecting him to get behind me and be happy for me. Instead, I got a shrug. That really hurt. And things changed. For the worse.”

Colbert’s grades plummeted. His behavior worsened. And his life quickly spun out of whatever control he’d previously tried to exert over his circumstances, eventually ending with him becoming homeless at the age of 16. And yet the story of Damon Colbert was far from over. In the end he would achieve incredible things, including serving in the U.S. Army for four years, marrying, and becoming a father to twins, and receiving three degrees from Monmouth University, including his doctorate in educational leadership last August. But before we get there, it’s important to understand how Colbert got there, because his struggles are also the source of his inspiration.

By the age of 16, Colbert’s performance on his high school’s football field had propelled him to local celebrity status. As a defensive end, Colbert set a new school sack record with 29 tackles. He was adored—at least during the fall. “Anything outside of that,” he says, “was horrible.”

Colbert was missing countless days of school, and when he did show up, he put forth the bare minimum to keep his head above water. Meanwhile, outside the classroom, he’d started “running around with the wrong people.” He was drinking, smoking weed, and often not coming home until the early morning hours, if he came home at all.

“My mother was overwhelmed with struggling through her substance usage, caring for my sisters, and trying to stay strong through heartache,” says Colbert. “My dad just left his family, and my mother had no support, no family around. It was just her and us, and my behavior at the time was completely out of line. I didn’t follow any rules she put forth to establish order in her house.”

Eventually his mother gave an ultimatum: Be home every night by a certain time or leave. And so, he left.

For almost the entirety of his senior year of high school, Colbert was a teenage nomad. He’d sleep wherever he could—friends’ couches, abandoned cars, train stations, alleyways, emergency rooms. He even made a regular practice of setting his watch alarm for 5:30 a.m. so he could use a tucked-away bathroom inside Monmouth Medical Center to wash himself, get changed, and brush his teeth before the morning rush of medical staff arrived. What’s perhaps most striking is that Colbert didn’t really give any of this a second thought.

“It felt normal because that’s all I knew. I wake up and I survive and I go to school. It wasn’t a matter of wishing I could live another way because there was no other way to compare it to,” says Colbert.

“I just remember thinking, ‘All right, things will get better because maybe when I’m20 or 21 I’ll be in the NFL and have a nice house and everything will be fine.’ I thought that would just happen. No work. No direction. No plan. Life was just going to take care of itself.”

For a short while Colbert’s sudden homelessness came with a rush of adrenaline and newfound freedom. But this didn’t last long, and he eventually needed to summon a robust work ethic in order to survive. He took jobs wherever he could find them. A gig at JCPenney. Pushing carts at FoodTown. Working for the city of Long Branch on the back of a garbage truck. Whatever it took.

“I wasn’t a career criminal and I was never scared of work. Faced with survival and having to eat and have a roof over my head all pushed me to get jobs,” says Colbert. “But I didn’t take anything into context. I was blind to whatever the outcome was. I was living in the moment and not seeing past it.”

Colbert spent much of the next decade in various stages of homelessness, spanning multiple states, and the surreal, sinuous path of his life during that time contains more multifarious experiences than can be chronicled here. But suffice it to say, after working odd jobs and enrolling for brief stints at two different colleges in the South, Colbert found himself, at age 27, back in New Jersey.

“My problem wasn’t about getting a job. It was that I didn’t know how to live up to my responsibilities. All I knew was get money, get a room,” says Colbert. “And I was drinking and smoking the whole time. My lifestyle was similar to an addict. I moved back home to try and make sense of everything.”

Colbert’s life didn’t spontaneously improve when he got back to New Jersey, but it did mark the beginning of the end of his aimlessness. Shortly after getting a job at a produce warehouse in Long Branch, he met a young woman named America at a party. The next day he spotted her inside a fast-food restaurant, so he popped in to chat with the woman who would eventually become his wife.

Colbert at home with his wife, America, and children (from left) Damon II and Iyliana.

“I looked a mess—dirty jeans, two hoodies—but I just came up to her and said, ‘Hey, what’s up,’” says Colbert. “We started talking and everything was great. I was in a vulnerable state. I was technically homeless, heartbroken from my last relationship, and I think she could see my pain.”

By the age of 29 Colbert was living with America and finally embracing a stability he’d never known before. And as he watched his future wife work her way up the ranks to supervisor status with-in Monmouth Medical Center while he continued driving produce trucks, he felt he needed to do more. So Colbert made a pivotal decision to enlist in the Army.

“I knew that if I stayed on that job, I was never going to go anywhere,” he says. “I needed to get my [stuff] together. America was moving up. I needed to move up too.”

The Army changed everything. Following boot camp, Colbert was stationed in the 82nd Airborne Division in Fort Bragg, North Carolina, and eventually deployed to Haiti for six months to assist in the aftermath of a devastating earthquake in 2010. Colbert’s work there as a human resources specialist impressed his sergeant major so much that, when the officer’s unit was given orders to deploy to Iraq, he stopped Colbert’s orders to a new duty station and retained him for the Iraq deployment.

Here Colbert—typically effusive and unrestrained—becomes reticent. He doesn’t like to talk much about his time in Iraq, where he served until being medically discharged following an IED explosion.

“There are certain things I don’t want to open up for myself,” he says. “Prior to that deployment I was going to stay in the military for 20 years. I was doing excellent and it felt like I was where I was supposed to be. But by the end of my time in Iraq, I hadn’t seen my wife in over a year and I was extremely ready to come home.”

And, so, Colbert’s life took one last dramatic turn. Following his discharge for combat-related injuries in fall 2012, Colbert immediately started taking classes at Brookdale Community College and preparing to become a father. And while his time in the military had its mix of highs and lows, the overall experience was exceptionally transformative.

“I used to live by the mantra that a soldier only needs four hours of sleep, and that’s how I got my associate’s, bachelor’s, and master’s in under four years,” he says. “I was able to do that because that’s how I operated in the military. It’s the discipline that was instilled in me.”

After Brookdale, Colbert enrolled in Monmouth’s School of Social Work in 2014, where he went on to earn both his bachelor’s and master’s degrees by 2016, all the while guided by one abiding passion: to one day help kids who faced challenging circumstances similar to his own. “I don’t want kids like me to suffer through almost 30 years before seeing an opportunity to thrive,” he says. “I don’t want these kids to go through life blind for so long.”

Looking back, Colbert says he chose Monmouth because he wanted to challenge himself in an environment that was academically and demographically outside of his comfort zone. He wanted to walk amongst people with vastly different experiences than his own and, just as importantly, “to understand those perspectives while elaborating on my own experiences.”

With his graduate work complete, Colbert began working for the New Jersey Reentry Corporation, helping recently released inmates find employment and housing. After a year there, he accepted a position as a social worker for the Veterans Health Administration, where he currently case-manages homeless veterans throughout New Jersey.

Colbert decided to take one last educational leap in 2018, when he returned to Monmouth once more to earn his doctorate of educational leadership. For two years he worked on his dissertation, “Examining the Emotional Impact on Educators Working with Trauma-Affected At-Risk Youth,” which he completed last summer. And while he’s not entirely sure what the next step in his journey will look like, he knows that it will, in some way, involve helping children who were as disadvantaged as he was. Whether that means establishing a local after-school program, starting a nonprofit for at-risk children, or potentially working for a school one day, Colbert knows that some of his greatest accomplishments are yet to come.

“I’ve been through a lot—from the bottom of the barrel to the success I see now. I’ve done a lot of things I’m not too proud of. But on the flip side, there’s a lot I am proud of. I don’t think people should be judged on their past. Everybody has potential, and sometimes you just have to unlock that potential. My goal is to provide opportunities for kids to unlock that potential,” says Colbert. “No one is lost. My story is one of trauma, hopelessness, and struggle, but I like to think of myself as the potential of the struggle.”