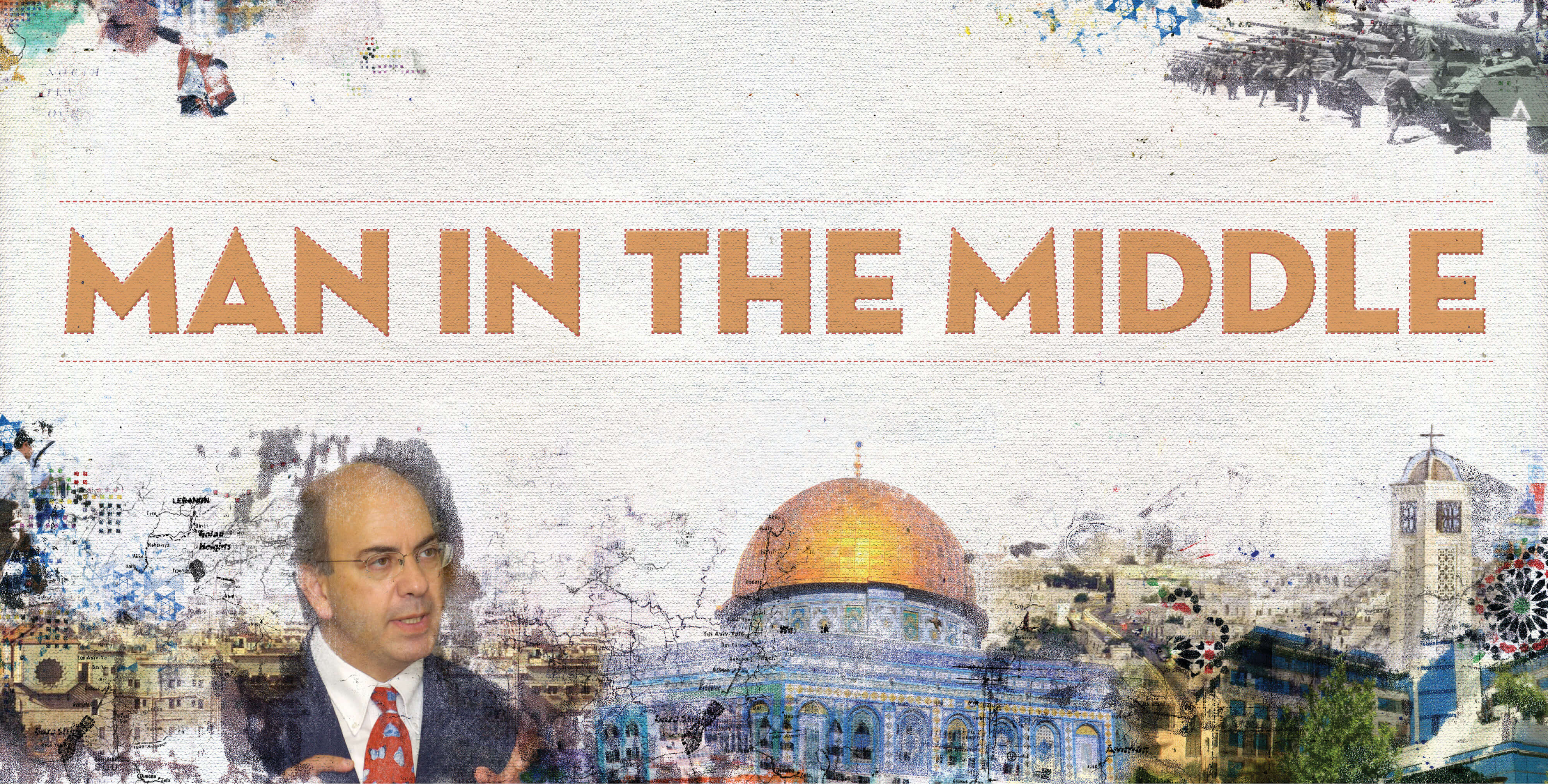

Man in the Middle

Saliba Sarsar has dedicated his life’s work to healing the differences between Israelis and Palestinians.

I grew up Palestinian Christian in East Jerusalem. My mother, father, grandmother, seven siblings, and I lived in a neighborhood called Al-Thori, just a few minutes south of the old walled city. My mother, who is now 90 years old, still lives in the house where I grew up.

Al-Thori is predominantly Arab Muslim—when I was a child, there were only four Christian families in the neighborhood—while Abu Tor, immediately to the west of Al-Thori, is home mostly to Jewish people.

I played with my Muslim neighbors. But I went to a Catholic school in the Old City called Collège des Frères where we spoke Arabic, English, and French. At home, we mainly spoke Arabic. (Jerusalem has always been a melting pot: My father was a printer who worked on an old Gutenberg press, and he would set the letters in Arabic, English, Greek, and several other languages.)

On the weekends, my siblings and I prayed at Mar Yacoub (St. James), the Greek Orthodox Church next to the Holy Sepulchre. I used to go to the Old City and act as a guide for Western tourists. I would show them where Jesus was crucified and his tomb; and I would be chased by the professional guides because I was taking their jobs away!

And this whole time—from 1949 until 1967—all of East Jerusalem was under Jordanian rule. It was not until the Six-Day War, which was fought from June 5 to 10, 1967, that East Jerusalem came under Israeli control.

No man’s land, which separated Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem from Israeli-controlled West Jerusalem, was a few hundred yards from my house. It was full of barbed wire and explosives. The Jordanian army stood face-to-face with the Israeli army across the border.

Then the war took place, and our lives changed forever. In a sense, that’s where the story really begins.

Crossing borders

Today, I can discuss the war ad infinitum. But as an 11-year-old, I didn’t know the full details of what brought it about. I knew there were some demonstrations in the streets and a lot of movement of soldiers. And when the war was almost upon us, able-bodied men came knocking at our door and said they needed to dig a trench in the garden that ran behind our house and the houses of our neighbors. They wanted to be able to move safely through the neighborhood without being exposed to enemy fire, so they came and dug up our garden. That’s when we knew that something serious was going to happen.

When the guns began firing, my entire family congregated in my parents’ bedroom, which was a safe space with thick walls. The fighting was heavy because we were close to the border. One of the kids I played with was killed: He went out in the garden to look at the fighter jets, and a bomb hit him. He died right then and there. He was 12 years old. Another neighbor who lived within 50 yards of us was shot and killed.

By the second day, things were intolerable; the house shook, and you could smell cordite and explosives. A neighbor urged us to evacuate, but we couldn’t open the front door. We had to lower a ladder from the garden to the street behind the house. My parents had us hold each other’s hands, and I held my brother Michael’s. We took refuge in a mosque—people were crying and somebody had a wound of some kind, probably from a bullet—and my mom had to go back to retrieve my eldest and youngest brothers.

At that point, Michael and I became separated from the rest of our family.

He and I continued walking with the crowd, which led us directly toward the Jericho area. We spent the night in another mosque and then came across a Greek Orthodox monastery in al-Eizariya (Bethany), a town on the southeastern slope of the Mount of Olives. We saw the gate and the cross shimmering in the heat of the day. The door was open. A nun ushered us in.

We shared what food we had—we had some bread and cheese, and the nuns made us soup—and we stayed there for two or three days. Then a couple who lived close to the monastery, and who knew my godparents in Jordan, took us in. We spent a few more days with them, and then the war was over. Michael trekked back to find out what had happened to our family and ran into them on the way.

They had stayed with a family in Beit Sahour, a town east of Bethlehem. They thought I was dead. Eventually we all went back home. But our home had been totally transformed: We were no longer living in Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem. Our house, our neighborhood, our city was now part of Israel.

No man’s land was dismantled, and we were able to meet the enemy for the first time. We soon learned the enemy was really in our hearts and minds because the people we met were just like us. They wanted to live in peace, security, and prosperity. They were afraid of us just as we were afraid of them. I began to question why we have borders and why we make our lives so unnatural.

I also discovered my family’s roots.

A few weeks after the war, while helping my parents around the house, my eldest brother found a document written in a strange language. My mom eventually explained that my father, George Sarsar, had actually been born a White Russian named Ivan Danilov. According to family lore, he was in fact a prince. The document my brother found was his Russian baptismal certificate. He was adopted by the woman I called my grandmother.

It’s hard to know why my parents didn’t tell us earlier about my father’s origins. Perhaps they felt we were too young to understand and wanted to wait until we were more mature. Perhaps they were acting out of deference to my adoptive grandmother, who lived with us. Or perhaps it was because the culture and society in which we lived did not fully embrace the idea of adoption, and not telling us was their way of protecting us.

Over time, I also learned that my mother’s father—my grandfather, who lived in West Jerusalem—was Greek. I believe my older siblings already knew this, but I was too young to have been aware of it. I only became cognizant of my mother’s ancestry as I got to know the secret of my father’s.

As a result of the war, therefore, I had crossed two borders: a physical one as well as a psychological one.

By the second day, things were intolerable; the house shook, and you could smell cordite and explosives.

Love Thine Enemy

Several months after the war, a Western man moved into the house next door. His name was Israel Hadany. Soon enough, his girlfriend, Brigitte, joined him. I found out that he was Jewish and Israeli. “Oh, my God!” I said. “The enemy is living next door!”

But that enemy became a member of my family. Israel and Brigitte married and had two sons, and they began spending much time with us. When the parents were busy, we took care of the children. When we cooked, they ate our food; when they cooked, we ate theirs. We became close friends and remain so to this day.

From the age of 12 or 13, I grew up in that type of environment: Christian, Muslim, Jewish. So I was able to develop this idea of inclusion, and of loving thy neighbor—and thine enemy—as thyself. Because there was no longer the issue of an “enemy”: Whether it’s across a border or the person living next door, we are one community, one family.

I’ve come to terms with that period of my life by writing about it, by teaching, by reaching out to the Other, and by trying to overcome the border. Crossing into the unknown, physically and psychologically, is something that I have come to know very well.

Recreating My Jerusalem

I came to the United States in 1974. A Methodist minister, Rev. John Grauel, was my visa sponsor, and in addition to my own family, several American families helped support me, showering me with care and love.

After graduating from Monmouth in 1978, I did my doctoral work at Rutgers. My interest turned to politics and history, and I wrote my dissertation on the psychological makeup of Egyptian President Anwar al-Sadat: why he made the decision on November 19, 1977, to visit the land of his enemy—Israel—to seek peace. He, too, crossed both physical and psychological borders.

When I came to work at Monmouth, in 1985, I tried to recreate my Jerusalem here—to work with all sides to benefit the common good, whatever that may be. Because an important part of crossing the border, whether in Monmouth or elsewhere, is education: How do you educate people and empower them to actualize what they hope for?

Project Understanding, which ran from 1992 to 2002, and the Monmouth Dialogue Project, which ran from 2007 to 2015, were direct manifestations of that. Jewish Americans and Arab Americans (Muslims and Christians) met on a monthly basis at the university and in each other’s homes. We talked openly about the issues that separate us, but also about what brings us together. We talked about the meaning of our faith traditions, about Israelis and Palestinians—what separates them and what is common to them—and about the dignity of difference. We took trips together, saw films, and hosted speakers.

In 2004, at the request of former university president Paul Gaffney, I created the Jewish Cultural Studies Program at Monmouth. I made certain to create an inclusive model that was hospitable to the various Jewish groups and faith traditions—Reform, Conservative, Orthodox—as well as to anyone who was not Jewish. It was meant for everybody, and it brought the Jewish community together.

Three years later, I brought Dan Bar-On, a Jewish Israeli psychologist who studied the Holocaust and Israeli-Palestinian relations, and Sami Adwan, a Palestinian educator, to campus as Fulbright Scholars-in-Residence. It was like coming to Camp David, where in 1978 President Jimmy Carter brokered the Camp David Accords between Egypt and Israel, and where in 2000 President Bill Clinton hosted peace talks with Israeli and Palestinian leaders. We worked together—me the Christian, Bar-On the Israeli Jew, Adwan the Palestinian Muslim—teaching, writing, and giving talks. It was a terrific experience, and our students benefited immensely from it.

I do not teach from a distance. In the early days, when I began teaching, I thought more in terms of abstractions. But now, I try to connect students to events and settings: How would you feel if you lived in Jerusalem? How would you feel if you were now living in Iraq or Syria? It’s tragic, but what happens in the Middle East is a laboratory for what we learn in the classroom. The students are fascinated, but they are also pained by what’s going on.

And when I speak about the Palestinian-Israeli conflict, I share with my students 10 posters that I’ve made, each representing a decade in Arab-Jewish and Palestinian-Israeli relations and each tied to my own family history. The students relate so well to this, It brings the history home and makes it come alive for them.

When the question of Palestine is resolved, the rug will be pulled out from under all of the extremists in the region.

Cultivating Peace

Today, the most reasonable outcome to the ongoing conflict is a two-state solution. A one-state solution will not happen because Israel will not accept to dismantle itself or to do away with its Jewish character or political dominance. If the Palestinians were to be given equal voting rights, then demographically, Israel would no longer exist.

And if Israel keeps taking more territory, Palestine will no longer exist. Then what would you do with the millions who live there? Do you keep them subjugated, under occupation? And if the Palestinians were to take over Israel, would they subjugate the Jewish state? It just doesn’t make sense.

This is why a two-state solution, whereby Israel lives alongside Palestine in peace, security, and prosperity, is the way to go.

The United States holds the key to resolving the issue, yet much of the work the U.S. president has to do is not on the Palestinians and the Israelis, but on Congress: He has to convince congressional leaders that there is no contradiction between supporting Israel and helping the Palestinians to actualize themselves.

That’s essential. The Palestinians have to choose democracy, pluralism, non-militarization, and neutrality because their emphasis has to be on developing infrastructure, jobs, education, health, and all the things that make a good life.

And when the question of Palestine is resolved, the rug will be pulled out from under all of the extremists in the region. There will continue to be pockets of them here and there, but they will not be able to sustain themselves. Their own supporters will abandon them because those supporters will be participants in the movement for peace: The surrounding Arab countries—Egypt, Jordan, Saudi Arabia and the other Gulf states, Morocco, Tunisia—would love to have peace, and once the United States, Israel, and Palestine start laying the groundwork for it, then those countries will come along.

But while that is happening, the political leadership must train their people to work for peace, and to expect it. Because once an agreement is signed, peace will not be lived unless it is cultivated. And leaders at all levels of society—parents, educators, religious leaders, civic leaders—must come to terms with the Other.

As I always say, Israelis and Palestinians will be neighbors forever. The sooner they understand that, the better.