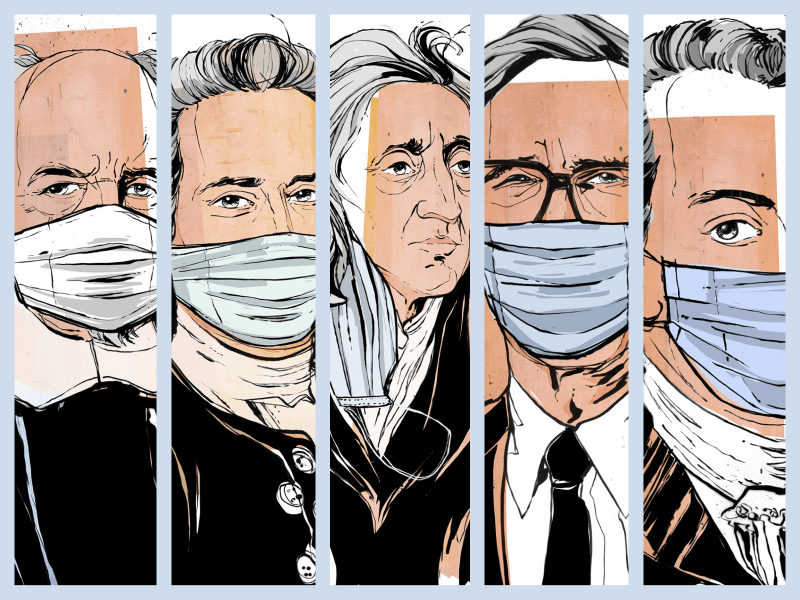

Free To Die or Forced To Be Free?

What the most influential social contract theorists might say about today’s mask mandates.

Whether you’re for or against them, mask mandates get to the heart of the social contract—that centuries-old idea that citizens’ political obligations depend upon an implicit agreement among the people to form the society in which they live.

So we asked an expert on social contract theory—Kevin Dooley, Ph.D.—to help us understand the history of these agreements in the hope it might inform the current debate over mask mandates. Dooley, an associate professor and chair of the Department of Political Science and Sociology, is the author of States of Nature and Social Contracts, which examines the ways the dominant historical figures employed the metaphor of the social contract to express their views of equality and freedom. Here, he gives us a primer on the theories of five of the most influential social contract philosophers and what they might say about today’s mask mandates.

Thomas Hobbes

Hobbes was one of the founders of modern political philosophy. His theories culminated in his masterwork, Leviathan, published in 1651, which concerns the structure of society and the role of legitimate government.

THE 101: Hobbes argued that before the establishment of any social contract, life is essentially miserable. According to him, we would eventually get sick and tired of being sick and tired, so we would create a powerful central government in order to live freely and not be subject to the “war of all against all” that exists, in his opinion, in the absence of an ordered society.

ON MANDATES: Hobbes would see no violation of our liberty, says Dooley, because Hobbes believed we ought to submit to the authority of an absolute sovereign power. If that power says we must wear a mask to stop the spread of a deadly communicable disease, then so be it.

Jean-Jacques Rousseau

The Genevan philosopher influenced the Enlightenment, the French Revolution, and the development of political, economic, and educational thought during the 18th century.

THE 101: In Rousseau’s social contract, each person enjoys the protection of the state while remaining as free as he or she was in the state of nature. The key to this is what he called the “general will,” which is the collective will of the body politic taken as a whole about how things must function for all citizens to be free. Under the right conditions, citizen legislators will converge on laws that correspond with the common interest. In other words, if we submit ourselves to the authority of the state collectively, we’ll get security and live as free as we were before we agreed to create it.

ON MANDATES: Rousseau would definitely be in favor of a mask mandate, says Dooley. Rousseau’s belief was that once all opinions are shared in a free environment after we turn over our individual rights, we can generate a consensus among all individuals. Those who still don’t agree can be “forced to be free” in order to maintain our security and general level of freedom in our shared society.

John Locke

The Oxford academic’s 1689 work, Two Treatises of Government, made foundational contributions to modern theories of limited government, ideas Thomas Jefferson incorporated into the Declaration of Independence.

THE 101: For Locke, the human ability to reason is the basis of our natural rights. His idea of the social contract consists of a limited government that safeguards life, liberty, and the pursuit of property. In his view, government resembles a trust, in which the citizens are both the creators and beneficiaries who get all the good stuff from it, while the government (the trustee) carries out the will of the people.

ON MANDATES: Although Locke emphasized individual liberty, he endorsed mandated military service, and because of this, Dooley believes Locke would likely be OK with mask mandates. Locke’s reasoning might be that if a communicable disease could decimate the population in a way similar to or worse than war, then it’s reasonable for citizens to accept a mandate designed to stop that destruction.

Immanuel Kant

The German philosopher continues to exercise significant influence in metaphysics, epistemology, ethics, political philosophy, and aesthetics.

THE 101: Like Rousseau, Kant believes we’re all free and equal in the state of nature, and that we need to expand legal requirements that protect individual thought and action. The key to Kant’s social contract is his “categorical imperatives.” He believes that humans fully understand that there are certain things that have to be made unlawful—murder, theft, sexual assault—because you can’t create a society that sustains itself on these kinds of behaviors.

ON MANDATES: Based on that reasoning, Dooley thinks Kant would include a deadly pandemic in his list of things that are wrong for a functioning society to allow. For Kant, the protection of life is a categorical imperative; societies literally can’t survive if they’re built on death. And in the midst of a pandemic that is killing hundreds of thousands of Americans, you can’t have a foundation where everything is eroding before your eyes.

John Rawls

The American political philosopher’s most famous work, A Theory of Justice, describes a society of free citizens holding equal basic rights and cooperating within an egalitarian economic system.

THE 101: Rawls argued that the way to think about our rights and the social contract is to imagine what life is like in a state of nature, but do so from behind a “veil of ignorance,” where you don’t know what personal traits are beneficial for the society into which you’re entering. He reasoned that we would all be afraid that life’s lottery would dole out a result that would leave us destitute, homeless, or disabled in some way. Therefore, we would create a social contract that includes strong social safety nets to protect the least advantaged in society because we might end up being one of them.

ON MANDATES: Given Rawls’s penchant for protecting the least advantaged, Dooley believes that Rawls would support a mask mandate because, as rational citizens, we know it could have been us who were among the most vulnerable to a deadly communicable disease like COVID-19.