Down the Rabbit Hole

Graduate student Sara Aniano researches the far-right rhetoric of conspiracy theories despite the challenges and risks.

In 2020, Sara Aniano started her master’s in communication studies at Monmouth just as the COVID-19 pandemic was about to disrupt everything. Amidst the uncertainty, Aniano found herself with a lot of time to contemplate what she wanted to do when she finished.

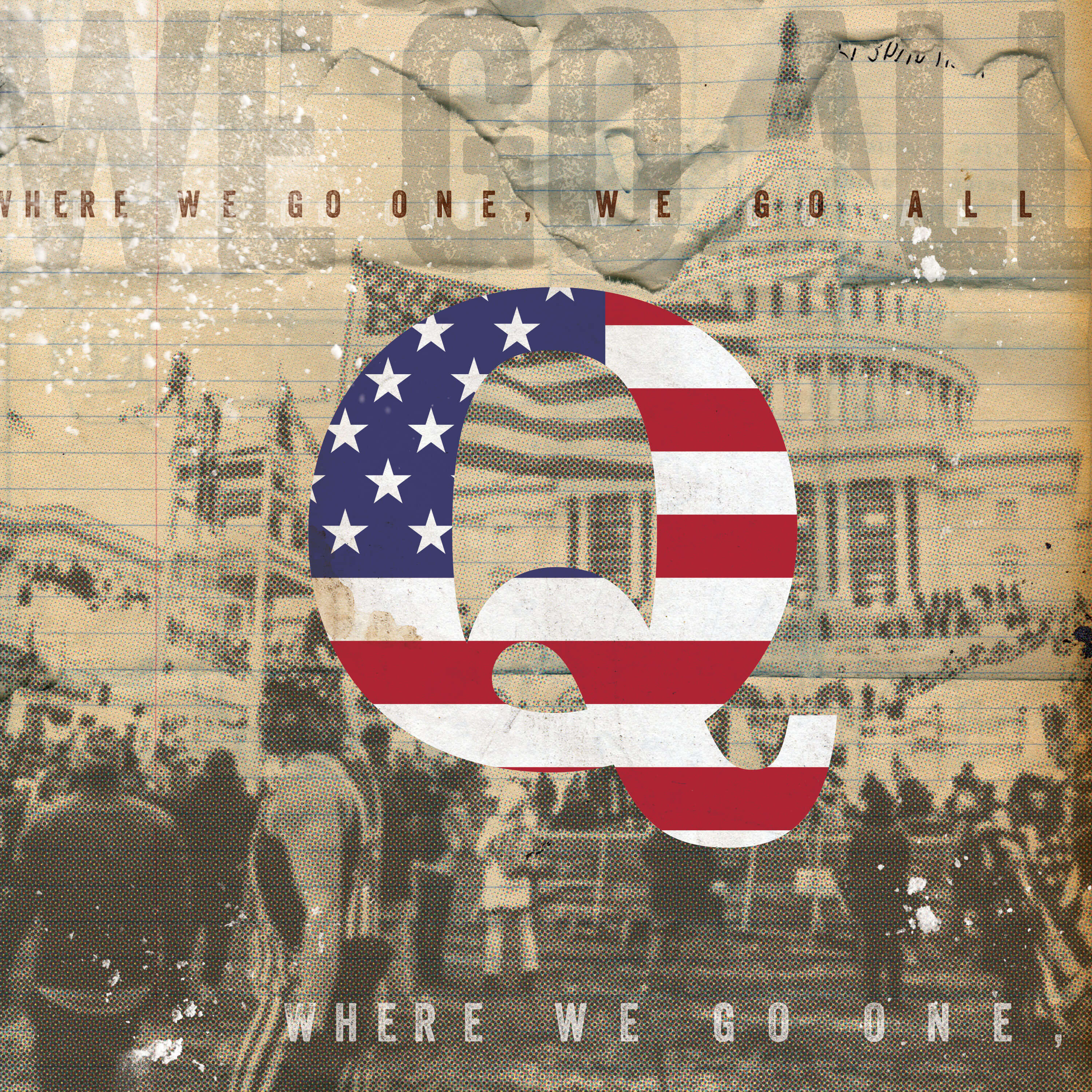

Then one day a friend told her a story about celebrities drinking the blood of children—a favorite topic of the QAnon conspiracy communities.

“I fell into the same rabbit hole a lot of people fell into during that time,” says Aniano. “But instead of believing it, I found it to be this really fascinating communication event that could pose really big problems for the future.”

Aniano, who worked in marketing for nine years before beginning her master’s degree work, was already familiar with effective social media strategies—core parts of online conspiracy theories—so she decided to make the machinations of QAnon the focus of her master’s studies.

“My thesis is on QAnon Instagram comments leading up to the Capitol riots of Jan. 6, 2021,” says Aniano. “I’m studying the online rhetoric of far right groups to see what kind of warning signs we can identify while highlighting the accountability required of both big tech and mainstream media.”

In her thesis, “Conspiratorial Communities: A Rhetorical Analysis of QAnon Instagram Comments Before the Capitol Riots,” Aniano presents evidence for how conspiracy theories about election fraud were successfully spread on public Instagram accounts.

“That’s worrisome because they’re readily accessible to everybody,” says Aniano. “You don’t have to be particularly tech savvy to read some misinformation on Instagram and find it believable.”

Equally worrisome for Aniano is being a researcher who presents her real identity online.

Last year, when Aniano wasn’t as experienced as she is now, she shared the username of a conspiracy theorist on Instagram who was posting from her public account. That person found out and shared all of Aniano’s content from Twitter, including her picture and real name.

“Commenters quickly branded me a satanic pedophile-supporting communist and said that I only got hired because I have Jewish on my résumé,” says Aniano. “And I’m not Jewish, by the way.”

Aniano has a thick skin, so the epithets didn’t bother her; the worst part was her lack of control over it.

“We did everything we could to report this account, but it never got taken down,” says Aniano. “The fact that Instagram was unwilling to help me, when I had so much evidence of their inability to take down misinformation before Jan. 6, made me feel unsafe.”

Despite the risks, Aniano has steadily published her research both on Twitter and for the Global Network on Extremism and Technology, which is funded by the International Centre for the Study of Radicalisation at King’s College London. In the process, she has become a go-to source for major media outlets reporting on the topic, including NBC News, The Washington Post, and The Philadelphia Inquirer.

Aniano intends to continue the work on the rabbit hole she fell into when the pandemic hit.

“My mission is to prevent misinformation in the future,” says Aniano. “That’s a lofty goal, but I’d rather try than not try.”