At a Loss for Words

Maureen Dorment’s course on censorship helps students make sense of the current resurgence in book banning across the country.

One would be forgiven for momentarily thinking they’ve been transported to pearl-clutching, Gilded Age America as they read today’s headlines regarding book banning in school libraries across the country. But instead of Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Leaves of Grass, or Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, today it’s works like Maus, And Tango Makes Three, and A People’s History of the United States that are drawing the ire of some parents and politicians.

Just this year, a sweeping bill was introduced in the Oklahoma State Senate that would prohibit public school libraries from keeping books on hand that focus on sexual activity, sexual identity, or gender identity.

No, it’s not the 19th century, it’s the 21st; but there is nevertheless an “unprecedented” resurgence in the censorship of books, according to a report by the American Library Association.

With this growing movement by conservatives to control what children should learn about American culture, society, and history, we asked Maureen Dorment, senior lecturer in history and anthropology, to help us make sense of it all. Dorment tackles these issues through her course, Censoring Culture: Banned and Burned in the USA.

Tell us about the course on censorship you’re teaching.

It’s an interdisciplinary perspectives course that focuses on specific instances of censorship in American history, from post–Civil War America to as current as I can make it. The books that are censored change throughout time—there are some constants that are usually in there, but for the most part, they always change. Books that were censored in the late 19th and early 20th centuries are not canonical works of literature. The texts don’t change. So, what changes? The historical context. We have looked from the late 19th into the 21st century at changing historical contexts and the different aspects of censorship that surface in each of these.

I also have students watch films as part of the course, because most of them are not history majors, and they need to have some type of historical context. And I try to choose movies that will give them a sense of the time period that we are discussing, and that will provide them an avenue to look and say, Now, wait a minute, was this warranted? Was there a real fear, or was the fear manufactured? It’s all about the social, political, and cultural context in which the book is written and in which the book is read. For the most part, it’s because the book has ideas that might not be conventional; it contains ideas that people would like to suppress.

Why is it important that your course view banned books as products of a given historical and social context?

When we look back at people like J. Edgar Hoover, for example, and his censorship of the modernist writers like James Joyce, we tend to forget the context of the times. But this is post-WWI, just after the Russian Revolution. There were labor strikes in the United States. Fear of communism was real. And rightly or wrongly, some of the cultural authorities associated those writers with communism. I want students to understand that there might have been a genuine fear which might explain but hardly justify Hoover’s war on the moderns.

Why is your course relevant today?

I tell my students at the beginning of the semester that censorship is the gift that keeps on giving—there is something every week in the paper about the current state of censorship in this country. What’s going on right now in Texas and Tennessee is in keeping with this steady flow of censorship.

In Texas, we’re talking about the American history narrative. In Tennessee, with the censoring of Maus because of the nudity and graphic detail—it’s difficult to write about the Holocaust without graphic detail.

What is happening now is in direct relation to the election of President Biden, and the emphasis by conservative commentators on culture war. So this class is particularly relevant to the time we’re living in today. It’s been really good because we are discussing the past in conjunction with the present.

What’s the crux of the issue with book banning?

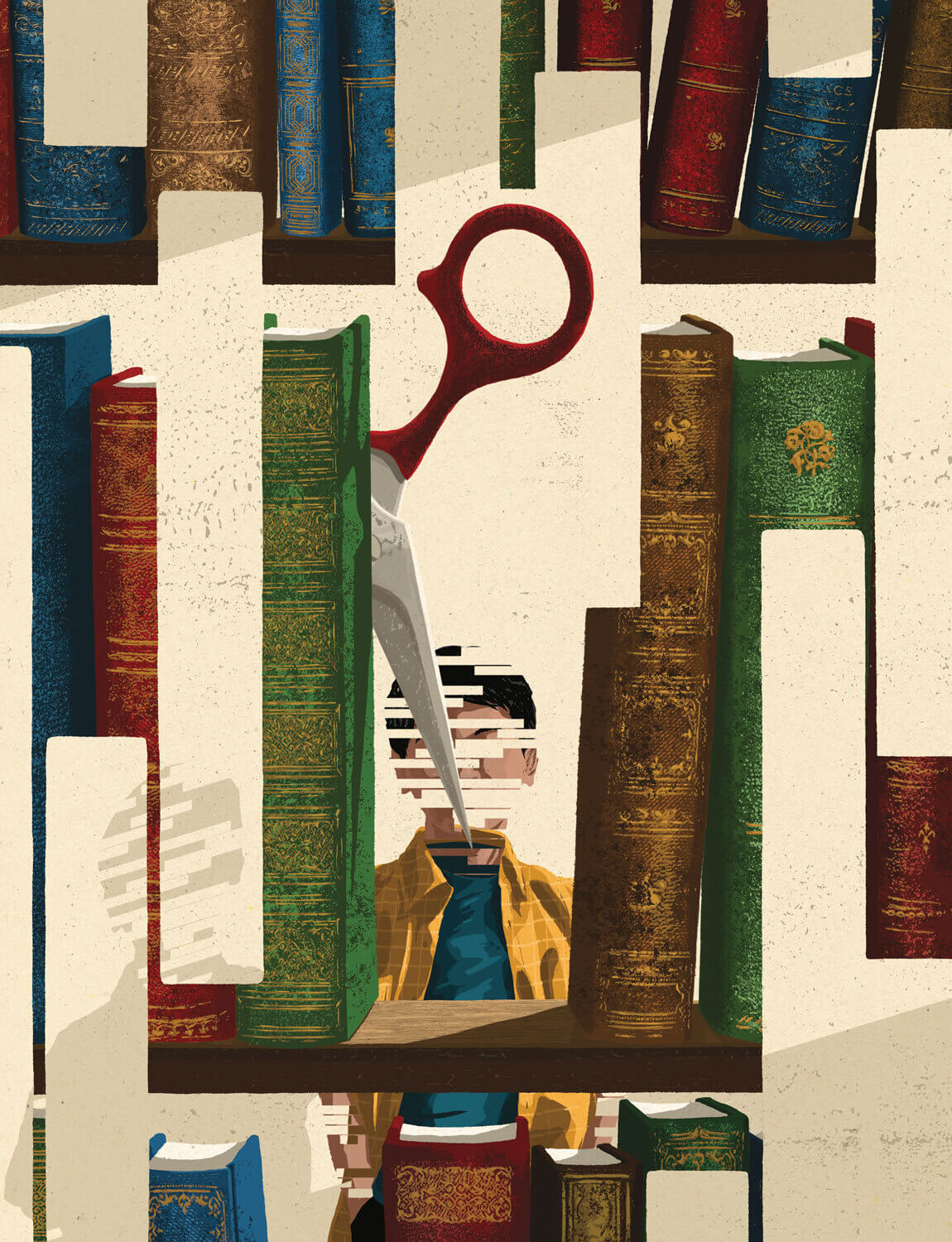

It’s the suppression of information. Books are material artifacts, but they are also carriers of ideas; when a book is removed from the shelf, someone is deprived of reading that book, and they are deprived of the ideas that are in it.

A democracy is predicated on a free flow of ideas and an educated population, and if that population is not supplied with all the materials that they need to make decisions, then that’s not good for a healthy society.

I tell my students at the beginning of the semester that censorship is the gift that keeps on giving—there is something every week in the paper about the current state of censorship in this country.

What’s the rationale behind book banning?

It is seldom about the censored artifact—it is more often about the historical, sociological, and cultural context that produced the artifact. It happens because there are those in some type of authority, religious or political, and the ideas are threatening to them and threatening to their way of life.

I always also tell the students that censorship is about power—who has it, and who wants to hold on to it—and if there are books that threaten traditional values, traditional ways of life, then it behooves certain cultural authorities to censor them.

What are these traditional values, or traditional ways of life?

Before the Civil War, America was a very homogeneous society. But with the influx of immigrants, the freeing of the slaves, and the African diaspora to the north, the Victorian values that had held society together were being threatened. After WWI, they were threatened even further.

I always explain to the students that traditional American values are centered on belief in God, country, and family, and whenever any of those three pillars of traditional values are threatened, the censors appear.

Traditional America, going back into the 19th century, was white Anglo Saxon Protestant. Then the Catholics came in, and they were initially a vilified minority. As we move through the 21st century, you see this white Anglo-Saxon Protestantism challenged by multiple religions, and this is very threatening to religious authorities. And then, of course, central to any country is the historical narrative. The question is, who gets to tell it, and how it is to be told. Do we do “America the exceptional country” or “America the oppressor?” Is there a way of squaring the circle that this was a country founded with very high ideals of liberty and equality, but it was also a country that was grounded in slavery, and a country that moved the Native Americans further and further west to almost complete extermination?

How are these “traditional values” being challenged today?

I think traditionalists believe it was a much simpler way of life, but it’s also about how they feel threatened. It’s not necessarily just religion. While it is sometimes ill advised to make generalizations, white Anglo-Saxon Protestantism, American exceptionalism, and a belief in the nuclear family work in tandem to attempt to define American values.

The traditional narrative is that America is exceptional. But since the 1970s, historians have been trying to rectify the triumphal narrative and see to it that our children are educated on the legacy of slavery, the civil rights movement, and the quest for African Americans to achieve the elusive goals of liberty and equality. There’s also the women’s movement, and Native Americans need their stories to be told, too. So the question is, how do you work these things into the historical narrative?

And in the traditionalists’ view, the nuclear family is under siege. Back in the 1920s, you had divorce and the single woman—the “flapper”—but now we have biracial couples and LGBTQ families.

Is there anything surprising you’ve learned by teaching this course?

In this day and age, it’s very difficult to censor anything. You can ban a book, but where there’s a will, there’s a way—someone is going to find that book on the internet. I had a student whose whole argument was that nothing can ever truly be censored because it will live on the dark web. He showed me how the dark web worked, and it was really quite fascinating.

There was also a recent article in The New York Times about a very entrepreneurial young woman in Tennessee who crossed the border into Kentucky and bought as many copies of Maus as she could possibly find and took them back to Tennessee and sold them at a profit. Censorship sells, censored books sell—and that’s the great fear, because of the ideas they contain.