A Snapshot of Who We Are

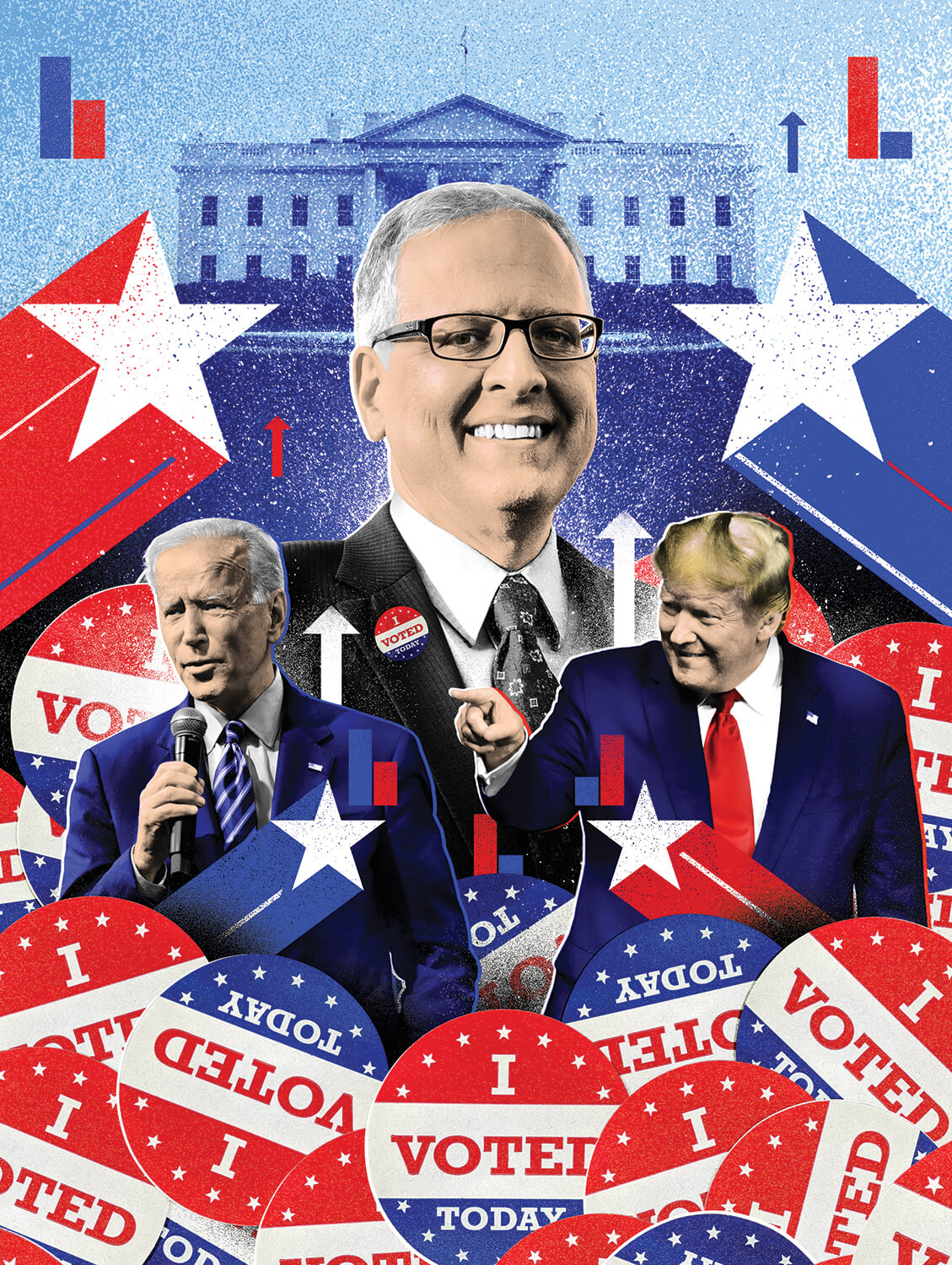

Patrick Murray, director of Monmouth’s Polling Institute, talks about a presidential election unlike any other.

Now in its 15th year of operation, Monmouth University’s Polling Institute has established itself as one of the most respected public opinion research organizations in the country. It consistently earns A-plus ratings from the venerable polling analysis website FiveThirtyEight, including most recently this spring, when it was one of just six polling operations out of 453 nationwide to earn the top mark. We asked the institute’s founding director, Patrick Murray, for his insights on what sets the Monmouth University Poll apart from the pack, what lessons were learned from the last presidential election, and what’s different about 2020.

Many people were surprised by the outcome of the 2016 presidential election. What lessons did pollsters learn from that?

Well, in the end, the polls weren’t off by any more than they normally are. It just so happened that in three particular states, the error was the difference between one person winning and another person winning. If you look back at 2012, we had a similar size of error in the battleground states, but none of those errors changed our expectation of who would win versus who actually won.

But one issue of importance in 2016 was education. In prior elections, there wasn’t a lot of difference between the way people with a college degree voted and the way people without a college degree voted. That started to shift in the 2012 election, but it didn’t shift enough to impact the polls. By 2016, it had shifted so dramatically—the gap was so huge between those without a college degree voting Republican and those with a college degree voting Democrat—that if you didn’t have the right balance of education in your polls that could throw off your results anywhere from one to three points. So now that it does matter, we’ve had to come up with ways to figure that out.

What else might people be surprised about when it comes to polling?

The bigger issue is that we’re talking a lot about which candidate is ahead and which is behind—but that’s only one question out of 40 that we ask in a typical poll. The other 39 are significantly more important to understanding the American psyche. What I’m interested in when I ask questions like “Do you believe that there are a significant number of secret Trump voters in your community?” is not a backdoor way of figuring out how many people are secret Trump voters; it’s a way of figuring out the mood of the electorate and what this could mean for the future of democracy in this country.

If people feel that Trump will win due to so-called secret voters, and the results come in counter to their hardened belief, that’s much more important to understand. I’m trying to find questions in our standard polling that can help us measure the things we can’t do in a typical poll that are driving the electorate. I’m trying to inform the public of the degree to which these beliefs exist and a sense of how entrenched we’ve become in our partisan identities. We don’t know the consequences of that because we haven’t seen something exactly like this in the past.

The problem is the politicians who have been willing to throw constitutional norms under the bus in order to hold on to their voter coalitions. This really shouldn’t be a left or right thing, but what usually happens is that it generally takes over one party more than another. What we saw with the Republican Party in 2016 was that Donald Trump didn’t control a majority of the party until after he won the nomination.

In 2016 people were thinking: Does my vote really matter? Is there really a difference between the two candidates? Should I vote for a third party? But they’re not thinking that in 2020. It’s a choice between a second term for Donald Trump—whether you want it or don’t want it.

How does this year’s presidential election compare to 2016?

We knew that there were going to be Obama-to-Trump voters in 2016; we just didn’t know exactly what proportion of the electorate they were going to make up. But the one thing that did surprise pollsters was the voters who would normally vote for Hillary Clinton didn’t show up at the polls at all. And that was because there was a big lack of enthusiasm for Clinton.

In 2016 people were thinking: Does my vote really matter? Is there really a difference between the two candidates? Should I vote for a third party? But they’re not thinking that in 2020. It’s a choice between a second term for Donald Trump—whether you want it or don’t want it. Most voters are there right now, and that’s much different than what we saw in 2016. Over the summer of 2016, we had a significant number of voters, over 20%, who were either undecided or were shifting around or thinking, “I’m voting for a third-party candidate.” But it’s less than 10% right now.

What sets the Monmouth University Poll apart from others?

The key thing is that we’re looking to ask fundamental questions of why voters behave the way they do, and not simply trying to answer topical questions or chase the news of the day—which we do, but we do that within the context of going out there and fully understanding the electorate. I’ve done a lot of work in the past on qualitative research, like focus groups. I go out and talk to people where they are. So you’ll find me at the Iowa State Fair; you’ll find me in a diner in New Hampshire. I do these things before we start an election season in order to understand the vernacular of what’s going on. Fortunately, I did quite a bit of it before COVID-19 hit, and I heard a bunch of information that’s making its way into our polling.

What did you learn doing that ahead of this election season?

That’s where I first started hearing a sentiment among some Republican voters that there were a lot of secret Trump voters who are going to show up on Election Day but not be captured in the pre-election polls. We have absolutely no evidence that that exists. We looked for that in our 2016 polling and they weren’t there. But understanding that belief is really important, not because it changes our polling numbers in terms of the outcome, but because it changes our understanding of what’s going to happen when we get the results back. There will be a significant number of people who expect Donald Trump to win and won’t accept the results if he doesn’t, and that’s what we’re trying to capture in our polling.

If there is one takeaway for readers about the polling process, what would that be?

Polling is a good barometer of where the public stands at any given point in time. It’s not perfectly precise, nor does it predict the future; but if you do dig deeper down into the poll, beyond the horse race numbers and the job approval numbers, you should be able to find information that helps you understand what proportion of the public is on one side of an issue and what proportion is on the other side, and who might be movable. It gives you a snapshot of who we are as a people.