Women Can Have a Little Power, as a Treat

In her latest research article, Professor Katherine Parkin shows how Sadie Hawkins Day has been used as just another means of control over women.

On the eve of International Women’s Day in 2017, State Street Global Advisors, one of the largest investment managers in the world, installed a bronze statue of a small girl named “Fearless Girl” facing off against Wall Street’s iconic charging-bull statue. Some said the statue was aspirational, while others described it as just another marketing ploy by corporate feminism.

One such detractor was HuffPost reporter Emily Peck, who wrote that when “a firm like State Street successfully co-opts feminism for marketing purposes,” women are “essentially ‘empowered’ to keep buying into the current system, despite the fact that it has so clearly shortchanged women (and men).”

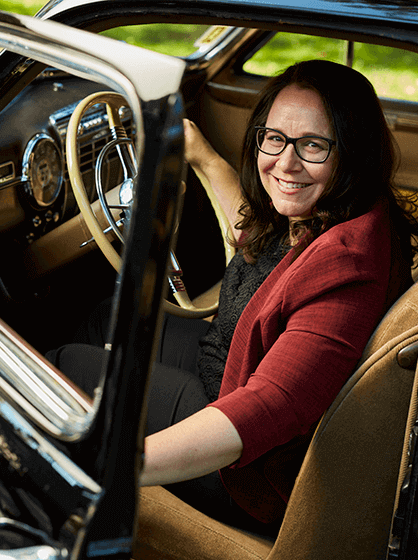

This idea of false empowerment is a concept that Katherine Parkin, a professor of history and the Jules Plangere Jr Endowed Chair in American Social History at Monmouth University, has studied extensively.

“False empowerment is the promise that women can gain power through events like these,” Parkin said, “and that promise is always premised on something that’s ephemeral, and is designed to say there’s something fundamentally wrong with them.”

***

Parkin’s latest research article in the Journal of Family History delves into this notion of false empowerment by interrogating the history of Sadie Hawkins Day, an American folk tradition originating from cartoonist Al Capp’s comic strip Li’l Abner that ran from 1934 to 1977.

Set in Dogpatch—a fictional town in the poor Appalachian hills—Sadie Hawkins was the daughter of the town’s mayor and the “homeliest gal in all them hills.” When she reached the age of 35 unmarried, her father created “Sadie Hawkins Day” to marry her off. The highlight of the day was a foot race where Sadie pursued the town’s eligible bachelors who, if she caught one, would be forced to marry her.

Not unlike Fearless Girl, in this story Sadie Hawkins has power not because she has asserted it or won it, but because it’s given to her by a man—Sadie’s father, as the mayor of Dogpatch, decrees it.

In her journal article, “Sadie Hawkins in American Life, 1937-1957,” Parkin argues that promising women power in choosing a boy to chase and pretend to marry ultimately reveals an ugly tradition, created by a man who disdained women and sought to sort them into desirable and undesirable categories, and invited America to play along.

Parkin also notes that, due to the popularity of the Li’l Abner comic, Americans embraced the notion of Sadie Hawkins Day with their own girl-chase-boy races and girl-ask-boy fall dances at high schools around the country. Nabisco’s Cream of Wheat brand even used Sadie Hawkins to sell their cereal, further entrenching it in American life.

***

Parkin’s research into Sadie Hawkins Day is part of a bigger question around the idea of false empowerment that she’s interested in.

Back in 2012, Parkin published another article in the Journal of Family History about a Leap Year tradition where every four years a woman could ask a man to marry her. In “Glittering Mockery: Twentieth-Century Leap Year Marriage Proposals,” Parkin argues that, again, the leap-year-proposal rule was a way for women to exert a little power over their romantic fate while still undermining their efforts to control their marital destiny.

In other words, Parkin argues that the appearance of power doesn’t necessarily mean that women accrue power in any meaningful sense.

“Sadie Hawkins purported to be an empowering opportunity for girls,” Parkin said. “The idea was that women should be happy because they have this empowerment with these exceptional opportunities, but it’s really a kind of safety valve to keep them under control the rest of the time—and I think our American culture is really dedicated to a variety of ways of keeping women powerless.”