Hidden in Plain Sight

Rediscovering the quiet legacy of Haslam Slocum and the iconic campus location that bears his name.

How do I get to Slocum Hall? This simple logistical query would likely stump even some of the longest-tenured members of the Monmouth University community, but if you’ve ever ventured into the lobby of the Great Hall, chances are you’ve already been there.

Tucked into the main campus’s central hub and marked only by an unassuming, blink-and-you’ll-miss-it plaque, Slocum Hall encompasses the Great Hall’s main floor, beginning just past the iconic mansion’s front entrance and ascending its three interior stories. The area, which was officially dedicated on Oct. 7, 1961, has been witness to decades of transformation, including Monmouth’s transition from college to university in 1995. It has hosted galas, presidential announcements, club events, and campus tours. Every day, hundreds pass through the space, likely without realizing its true name.

So who was Slocum Hall named for, and why does it matter?

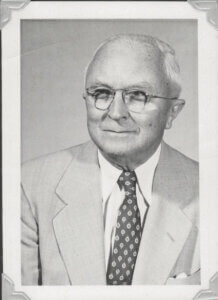

The history of the hall is intertwined with neighboring Long Branch, New Jersey, and begins when Haslam Slocum was born there in 1879. A lifelong resident until his death in 1958, Slocum graduated from the Long Branch public school system, operated a local fuel oil business, and was a respected civic leader and fixture in the community for nearly eight decades. In a final act of service to his beloved hometown, Slocum willed over $250,000 to local causes, including $100,000 to then-Monmouth College, marking the institution’s first-ever bequest.

Notably, the bequest contained no parameters for specific use and was intended only for “the general purposes of the College at the discretion of its Board of Trustees.”

“Monmouth College is very pleased with the splendid bequest of $100,000 in the will of Haslam Slocum,” wrote then-president Edward. G. Schlaefer in a statement made Nov. 6, 1958, noting that Slocum had been a very good friend to the College “in a quiet way.”

Schlaefer had spearheaded the initiative that saw Monmouth acquiring the Great Hall a few years prior; previously, all classes had been held at the local Long Branch high school. The Shadow Lawn mansion, which cost over $10 million to build in 1933 dollars, was eventually purchased by Eugene Lehman to serve as the home of Highland Manor Junior College after the now-landmark building fell into ignominious municipal ownership.

Schlaefer’s daughter, Nancy Schlaefer Bruch ’58, recalls that Slocum, or “Has,” as he was known to her father, had earlier made a gift of $1,000, which was one of the first significant donations toward the purchase of Shadow Lawn.

Slocum’s estate gift, which would be valued at nearly $1.1 million in today’s dollars, marked a turning point in Monmouth’s history. Once a humble junior college, the institution conferred its first four-year baccalaureate degrees in 1958 at the new Shadow Lawn campus, taking the first steps toward eventual university status. Over the next decade, Monmouth would also acquire the Guggenheim Memorial Library while continuing to grow its academic, athletic, and residential programs.

To honor those who helped usher in this new era of the institution’s history, Schlaefer commissioned plaques that would adorn campus with the names of individuals and groups who had a profound impact on Monmouth, including the likes of Mil- ton Erlanger, Maurice Pollak, and Slocum, among others. Gifts from these donors had “enabled the institution to provide more facilities and a larger curriculum,” Schlaefer said. He promised that as Monmouth continued to grow, it would “become the pride of the shore area.”

Slocum, for his part, had no particularly strong connections to Monmouth before his death other than a deep dedication to serving the local community in which he lived his entire life. Bruch believes that Slocum and her father had become acquainted through the Rotary Club.

Slocum proved to be exceptionally generous in his will, bequeathing his home to the city to be turned into a public park. He also bequeathed funds to the YMCA at Long Branch, St. James’ Episcopal Church of Long Branch, the West Long Branch Cemetery Trust, Monmouth Medical Center, and all employees still working at his fuel company at the time of his death.

Now a doctoral university on a 170-acre campus, Monmouth has transcended anything the pioneers of Monmouth College likely would have envisioned in the 1950s. Slocum’s then-unprecedented gift has quietly faded into history, but perhaps that’s the way he would have wanted it. His planned gift—the first in Monmouth’s history—was offered without fanfare or conditions and was intended simply to help the local institution provide greater resources to its students.

Ultimately, Slocum’s gift was a tremendous vote of confidence in the importance of the college to the region. His bequest proved to be instrumental to an era of accelerated growth of campus facilities, ushering in a new era at Monmouth and paving the way for generations to come—what Schlaefer correctly predicted in 1958 would be “the great wave of students who will be upon us in a few years.”

Though Slocum didn’t seek recognition, that doesn’t mean he isn’t due any. His generosity is a reminder that all gifts, big and small, have the opportunity to change the course of individuals and institutions alike. Slocum’s bequest came at a turning point in the University’s history, and, by setting the stage for Monmouth’s transformation from modest college to thriving national university, its impact still reverberates through the recently renovated Slocum Hall, where a new generation of students gather, grab a bite between classes, and study.