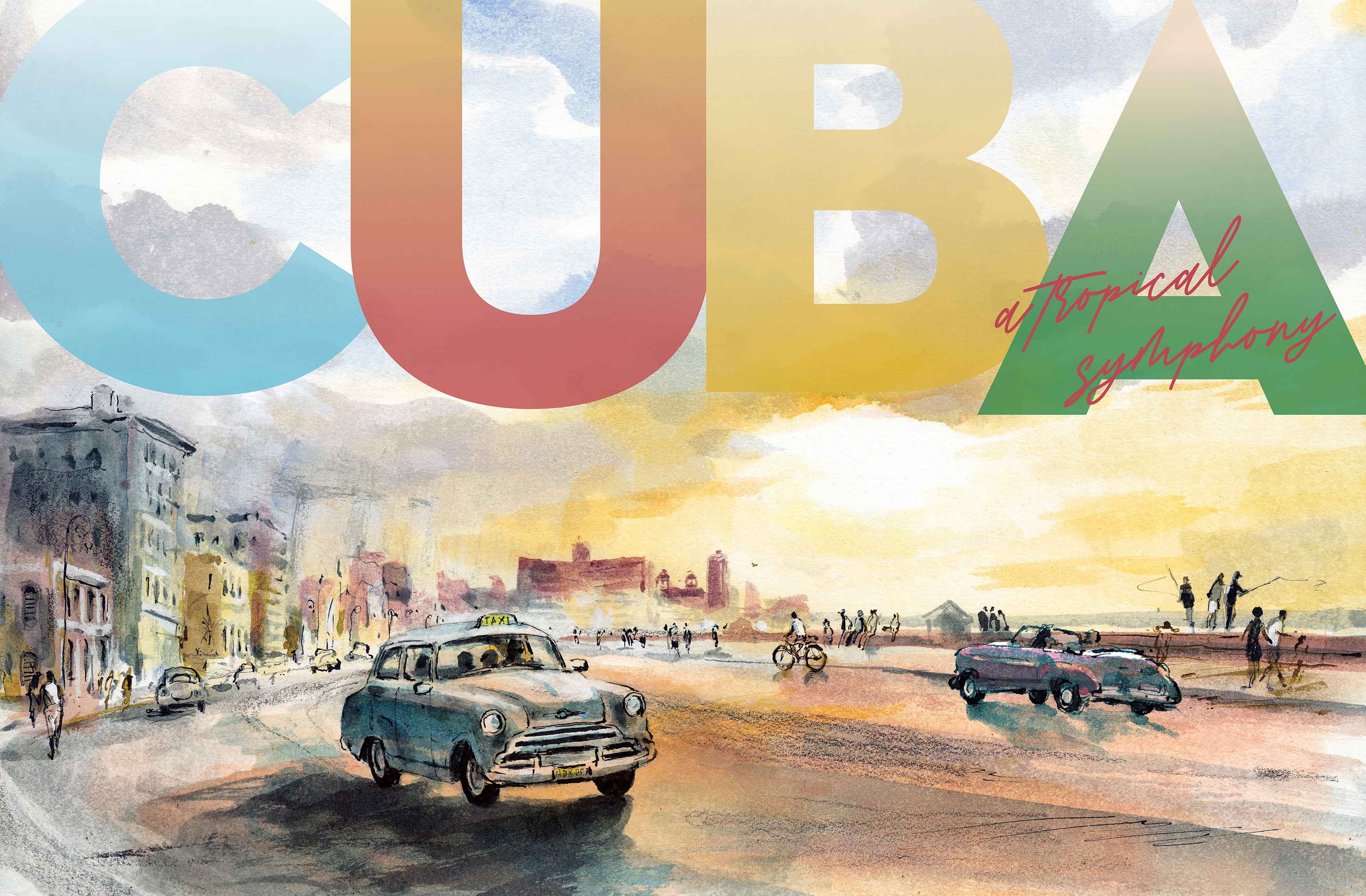

Cuba: A Tropical Symphony

Upon my arrival at the José Martí International Airport, I was struck with a realization: Cuba lives and moves at a different pace; it vibrates with a singular rhythm. If you want to get a sense of the real Cuba, you have but to adapt to those tempos and embrace the flexibility, openness, and richness of the unexpected. And of course, you need to know how to listen. The country is a symphony of voices that assault your senses at every level and in every context, but you must enter the concert with ears wide open so you can distinguish the different instruments and intertwined melodies.

I had been invited to Cuba to present my research on innovative ways of teaching literature, and so when I arrived in the island nation last June, the conference, VII Taller Internacional de la Enseñanza de las Disciplinas Humanísticas: “Las humanidades y la identidad cultural en el siglo XXI” (Humanities and Cultural Identity in the 21st Century), was my first stop.

There, the tongues of presenters from Cuba and around the world, as well as of those of the audience members, were unleashed, and voices of sundry colors and textures jumped from the papers to the open space of the Américas Convention Center. Some of them— sounding out the reactions—whispered, while others were more open to speaking out about the need for critical thinking, of a more creative and disruptive approach to teaching literature and the humanities. The worn-out voices of those who advocated for the status quo, those who, fearing changes, sought shelter in past rhythms and melodies, could also be heard.

But the overwhelming committed love for the word; for literature, culture, and education; and for the construction of people’s cultural identities spread harmony through the symphony of voices. As a fellow researcher[1] noted in her presentation on Cuban poet and statesman José Martí, in Martí, “teaching and real education intertwine with the struggles for the improvement of the human race.”

Martí’s thoughts indeed represent the continuation of a humanist heritage that considers education as a basic human right, essential to progress and individual and political freedom; his voice could not be left out of a conference highlighting the importance of the humanities, education, and strategies on how to reach the goals of the adopted United Nations Global Education 2030 Agenda of “ensuring inclusive and equitable quality education and promoting lifelong learning opportunities for all.” Martí’s words would be foremost on my mind throughout my journey through Cuba.

Voices Outside Academia

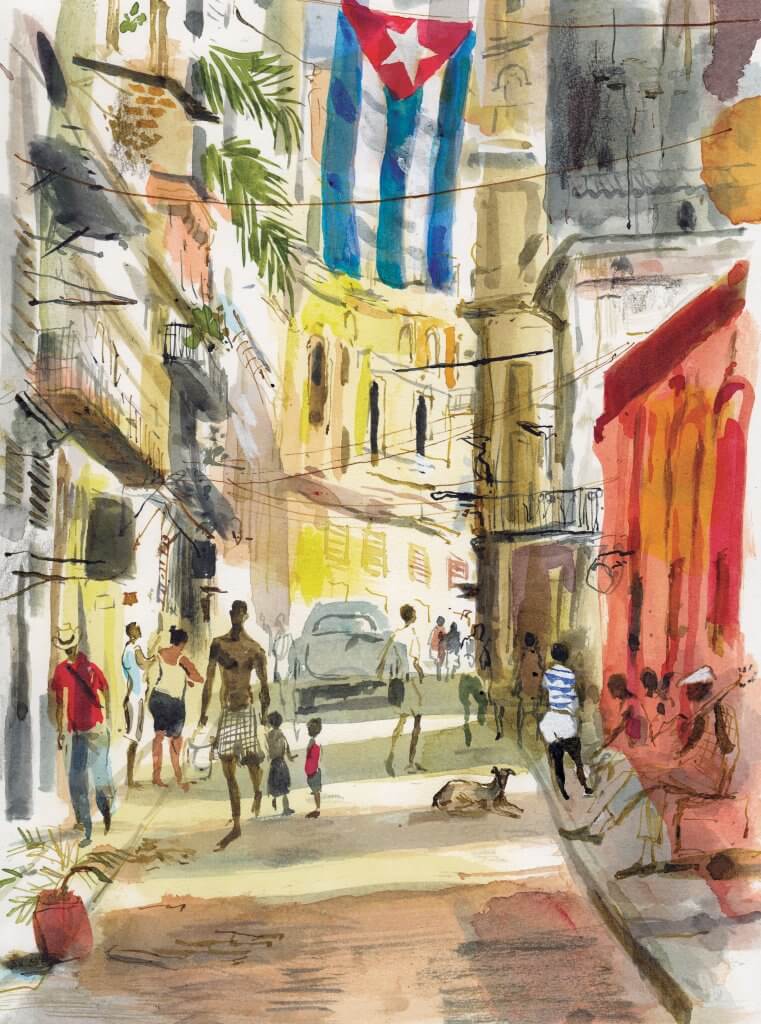

Besides being heard, Cuba’s voices can also be seen. They scream from the wounded walls of ancient palaces and exclusive buildings in old Havana, which today is home to the poorest of the poor in Cuba—those orphans of relatives in foreign countries, hence without access to foreign money, or those who left the countryside in search of better opportunities, sometimes three generations of families living in the same room. They scream, with dignity, for help, for the end of the suffering, for the right to dream of a better life and the means to make it happen.

The other buildings, the ones that have been renovated after the foreign investment was approved, serve as lodging for tourists who go to Cuba not to get to know the people, but to witness “the end of a revolution”; those buildings utter a different discourse.

Cuban voices spoke to us from the brilliant colors of the classic postcard cars of the ’50s, their drivers inviting you to take a trip back in time; from the old Havana; from the Vedado—the modern part of the city, its central business district and most affluent part; from the Hotel Nacional, which in the mid-’40s hosted Lucky Luciano and other mobsters; from the Plaza de la Revolución, or Revolution Square, where Fidel Castro used to address Cubans and political rallies still take place; from John Lennon Park, which in the ’60s sheltered the voices of young Cubans who dared to dream with him of a “life in peace,” disobeying their government’s prohibition on the Beatles’ music; and from the malecón, where Cubans of lesser means go to kill hot summer nights with families, or to fish, or to sell whatever they can to survive: cheap handicrafts, eggs, or raspados, a kind of slush with tropical syrups.

The People’s Voices

And while showing the landmarks, the chauffeurs—sons or grandsons of original revolutionaries—add their notes to the symphony of voices. While thanking the revolution for what it gave them—free education and medical coverage—their voices become gloomy and sour recognizing that they earn more as taxi drivers than as engineers, doctors, or lawyers. And they fear the effects of the embargo, and Donald Trump’s latest measures prohibiting the entrance of cruise ships to Havana, which decimated the number of tourists visiting the island, but also the internal embargo imposed by the restrictions of the Cuban government. They love their country; they do not want to leave, but they dream of a better life for their children and for more freedom to make that happen.

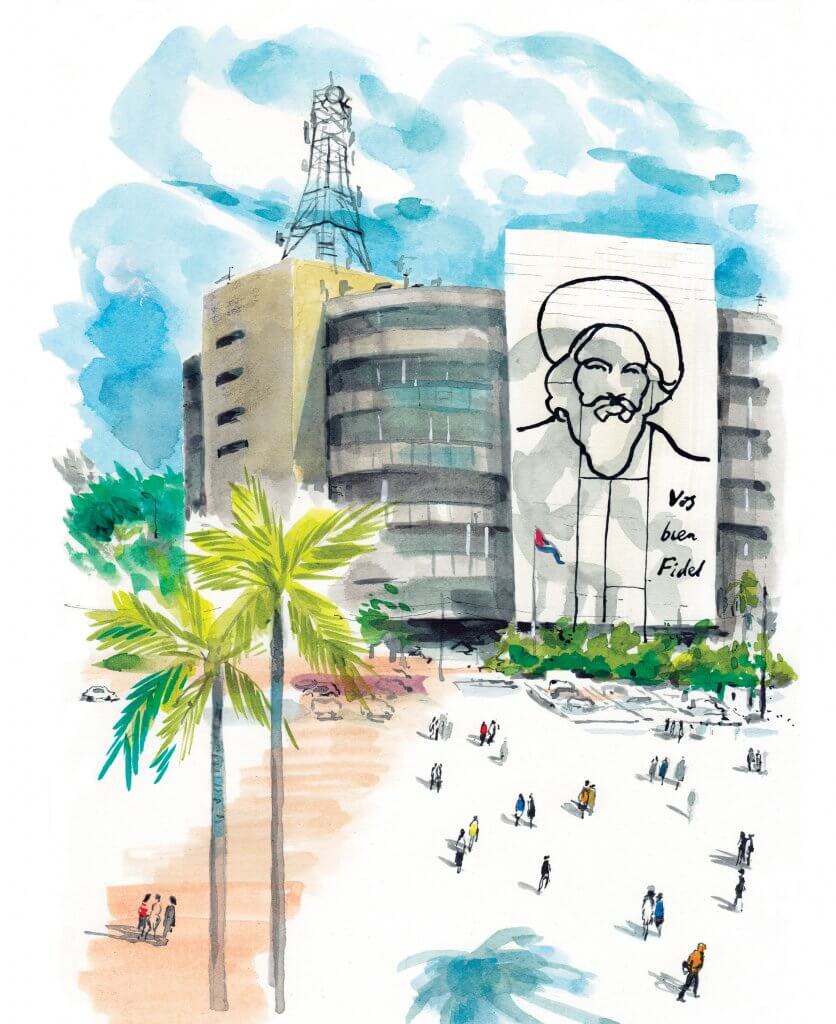

At the impressive and breathtaking Revolution Square, a mandatory stop in any visit to Cuba, we were surrounded by voices coming from every corner of history. Presiding, the Cuba of the Independence was embodied in the monument of Cuban national hero, José Martí. Facing Martí, enclosing the area where people who make history stand for political rallies, images of revolutionary heroes were embroidered with one of their idiosyncratic quotes: Camilo Cienfuegos with “Vas bien Fidel” (“You are going down the right path, Fidel”) and el Che with “Hasta la victoria siempre” (“Until victory always”). To the right was the remarkable National Library José Martí, home to Cuba’s and the world’s literary and intellectual heritage, where they gladly accepted copies of some of my books, a humble contribution.

The silent voices of Cubans absent from the Revolution Square, the ones of the geologists, pharmacists, attorneys, and so many other professionals with diplomas from the Universidad de La Habana, could be heard across the square. There, people waited at the bus station to tend to their daily business as tenants, waiters or waitresses, managers, or even as owners of an apartment for rent or a paladar (small restaurant) after Raúl Castro legally authorized the cuentapro- pistas (self-employed workers or literally, “on your own-ists”). Voices that, like the taxi drivers’, expressed their sweet and sour feelings for life in Cuba, their satisfactions and disappointments, their expectations and lack of hope. Voices interrogating Cienfuegos: When did we lose the path? Which is the right path?

Arts and Literature

A couple of days before I arrived in Cuba, the national poet Nancy Morejón, a longtime friend, was leaving for Ecuador, returning only on the last day of the conference, the only day she could meet with me. I was torn between meeting with her or going to the discovery of a treasure. I opted for the second, and do not regret it. After all, I can eventually meet with Nancy at any other professional meeting, but I will perhaps never have another opportunity to visit the premises of Ediciones Vigía, an independent publishing house located in Matanzas, Cuba.

Ediciones Vigía specializes in handmade books. Its artisans use collaged and repurposed materials such as recycled paper, buttons, yarn, fabric, dried leaves and flowers, and pebbles to put together a limited number of volumes—a maximum of 200 copies of each title are published. Today, these books are part of the collections at New York’s Museum of Modern Art and the Beaubourg in Paris, to name but two. These books of unique colors and textures make us hear the voices of both Cuban and international authors. Inside Ediciones Vigía, Martí’s omnipresent voice was calling me, as it called me from the José Martí International Airport, or the José Martí Nation- al Library, or the José Martí monument in Revolution Square, from the voices of the balseros, Cubans who lost their voices and their lives fleeing the country in search of a better life for their children.

I bought two bilingual books by Martí, not only because he represents a paladin of humanism, freedom, social justice, and education as means to build a more humane society, but because he embodies many of the voices of Cuba and Latin America, including a literary heritage that still informs us.

On the plane home, while pondering my experiences listening to the Cuban voices, whether coming in words from the people or in screams from the buildings, parks, and squares, I kept wondering: What will be the subsequent movement of this ever-changing symphony? Where are all those voices heading to?

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Priscilla C. Gac-Artigas, Ph.D., is a professor of Spanish and Latin American literature at Monmouth University, a Fulbright scholar, and a correspondent member of the Academia Norteamericana de la Lengua Española. Her attendance at the International Conference Humanísticas in Varadero, Cuba, and her further research in Havana, was made possible in part through a Scholarship of Teaching and Learning mini-grant from Monmouth University’s Center for Excellence in Teaching and Learning.

Notes

- Lourdes Díaz Domínguez, professor of literature at

the University of Matanzas.