A Changing India

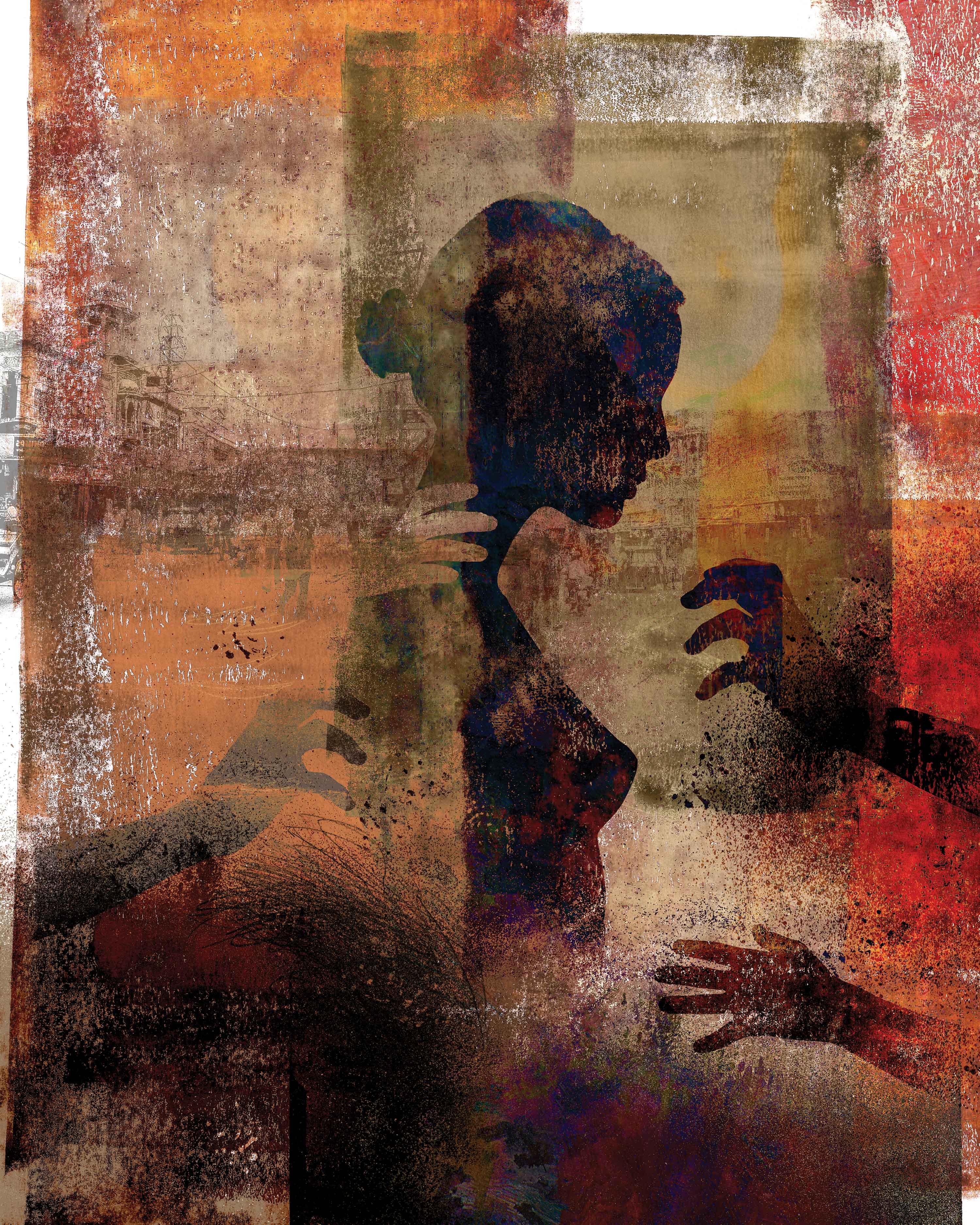

Can education and economic empowerment put an end to the gender-based violence that has plagued the world’s largest democracy?

It’s been said the most dangerous time for a woman in an abusive relationship is when she tries to leave it. The same could be said on a societal scale about women in India, who after centuries of subjugation are seeking more independence, but are being met with contempt and—in some cases—violence.

One of the most highly publicized examples of this was the 2012 gang rape of Jyoti Singh, a 23-year-old who worked the night shift at an IBM call center to fund her medical school education. Singh was returning home from a movie one evening when she was beaten and sexually assaulted by six men on a bus. She died two weeks later from her injuries.

The assault made headlines globally, and ushered in a greater awareness of, and activism and policy changes aimed at addressing, gender-based violence (GBV) in India. Yet the problem persists, with the gruesomeness of some of the acts particularly shocking. Just last spring in India, three teenage girls were sexually assaulted and then set on fire so they couldn’t identify their accusers.

Last fall, political science Professor Rekha Datta received a Fulbright Scholar Award (see sidebar) that enabled her to travel to Haryana, India, to study whether and how education and economic empowerment can help overcome GBV. Working with Participatory Research in Asia (PRIA), a New Delhi–based NGO, and research assistants from the Public Policy graduate program at O.P. Jindal Global University, Datta conducted focus group discussions with women and youth participants living in rural areas of Haryana. Those discussions provided insight into how families in Haryana’s rural areas feel about education and the roles of women in the changing Indian society.

Datta, who was born in India, says the country has changed dramatically since she left in 1985, largely on the crest of the information technology boom and economic liberalization. But in some ways, the more the country lurches forward as a leading world power, and new perspectives on GBV take hold, the more many traditionalists seem to tighten their grip on old-world values—a tension that has possibly contributed to continuing violence against women.

An example of this can be found in a documentary about the 2012 gang rape of Jyoti Singh. The film includes interviews with the men imprisoned for the assault, and it is clear they resent women who are advancing their careers, especially in the urban-based new economy. “These women are taking our jobs,” said one man. Another expressed the opinion that women should not be going out at night without a male relative.

“Because women are going out more, they’re more visible,” says Datta. And as more women work in the IT sector, at all hours of the day and night, it’s not uncommon for them to leave work at 2 or 3 a.m., making safety and security a big concern, she adds.

“In country after country, in case after case, it is not uncommon for rape allegations to be slid under the rug, or for organizations to not want to publicize them for fear of tarnishing their names. In the case of India, it’s no different,” says Datta. “However, even though things are beginning to change somewhat since the 2012 gang rape, the issue remains nuanced and complex.”

Datta says she began to look at the impact of education on gender violence after realizing she couldn’t study GBV without getting into the topic of schools. Haryana was an ideal location for her work: The state has been a leader in agricultural production and a beacon of advancement in agriculture and manufacturing, and has one of the highest per capita incomes in India. Yet due to the persistence of patriarchy and socially regressive norms, practices such as child marriage and discrimination against female children are common there. According to recent census data, Haryana has the lowest sex ratio of any state in India: 877 females to every 1000 males. The numbers are even lower for children: 830 girls to every 1,000 boys.

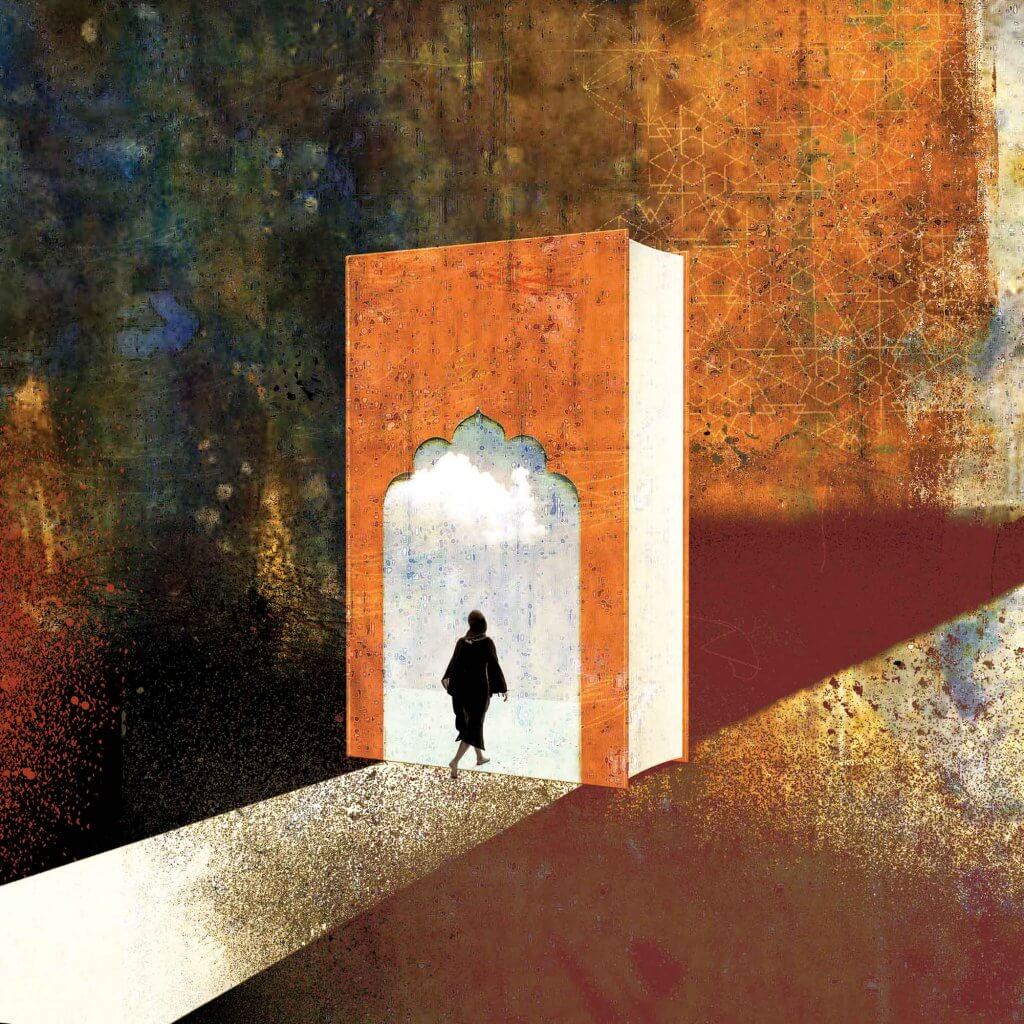

It is not uncommon to find that if you increase education, women will be treated more equally. “Economists such as Nobel laureate Amartya Sen have argued in favor of education as key to empowerment of both women and men,” says Datta. “The southern state of Kerala, for example, has the highest literacy rate in India at 94 percent, with an equally high female literacy rate of 92 percent. The Kerala model of development has been a result of the success of education and health policy.” And yet recent studies suggest that violence against women is not decreasing even as education is rising.

“And so that is another puzzle I wanted to explore,” says Datta.

Part of the dilemma is the complicated relationship India still has between gender roles and tradition as the country marches toward modernization and economic prosperity. Datta’s field work involved focus-group discussions with girls living in rural areas who want to change and become more modern, but whose families are hesitant and afraid of such a prospect. They fear for their daughters’ safety if they travel far from home to seek higher education or employment.

“India remains, for a large part, a fairly traditional society,” says Datta, adding that even the researchers were advised to dress in a sari or salwar kameez—a traditional Indian pantsuit—and a scarf when they went to interview students at local rural high schools.

Datta found that while the government has implemented incentives that resulted in more girls going to school, those students tend to leave upon reaching adolescence. She interviewed families in rural areas who agree it is a good idea to send their daughters to school, but only until the end of high school.

“Many of the mothers my team and I spoke with concluded that after they complete 12th grade, or higher secondary in India, girls do not need further education,” says Datta.

An exception, she found, are girls who show educational promise—but even then they can continue their education only at a local school. Attending college in a different town brings too many uncertainties. One big concern is safety—whether it be the roads, the transportation system, or the campus itself. The area lacks adequate safety for a woman being out and about.

“We were stunned to hear that some women felt that some of the victims of sexual assault were asking for it,” says Datta. “‘Why do you need to go out at odd hours?’ they asked. ‘Why do you need to go far away to college? You will be safe in your community and township’ was their conclusion.”

Datta says she recognizes that where and for how long a child goes to school is a familial decision, and one in which government should not intervene. But issues of safety and security are public policy questions, she notes.

“That is something that—as individuals, as citizens—girls and women can and should be able to demand of their government,” she says.

Gender violence occurs in both the public and private spheres, says Datta. Along with safety and security of women in public spaces, intimate partner violence, child marriage, misogyny, and discrimination against girls and women continue to be ubiquitous problems. The impact of such violence is well researched and documented. The challenge is how to overcome it.

“Education remains an important source of empowerment to overcome violence,” says Datta. “Education can empower both men and women to realize the importance of gender equity. Only when we learn to respect women as equal citizens and individuals will we be able to combat this scourge of gender violence at all levels.”

Moving the dialogue from a family matter to a public policy question is something Datta is attempting to incorporate into her work.

“I think these changes will come,” she says. “Along with laws and policies, cultural and social changes will help bring such change.” But it will take time, she adds. “The hopeful thing is that change is already coming, albeit slowly and in pockets.”

When asked what impact she hoped to make, Datta says she questions that herself sometimes. In the end, she hopes to be an “instrument” of change—that by observing and sharing her observations, and by hearing women’s stories and sharing them, she can raise awareness that will hopefully inform public policy.

During one of her previous visits to India to do field work, Datta met a woman who didn’t know how to read, and who would go to work every day by bus. Because she couldn’t read the signs on the front of the buses, she would have to ask someone what it said. Some people would ignore her, others would scowl, and occasionally someone would help. It was humiliating, the woman said. But once that woman learned to read, she felt empowered.

“The ability to read gave her dignity and self-respect,” says Datta. “This is what empowerment does. With education, an empowered woman is able to stand up against discrimination and gender violence.

“As a social scientist and an educator, I cannot claim to bring about significant social change,” says Datta. “But I can share the voices of such women so that we can create a better and more empathetic understanding of women who face discrimination and violence, and how education can bring positive change.”