Bell Labs to Bell Works: How one man saved the historic site and made it a tech mecca

Michael L. Diamond

Michael L. Diamond

HOLMDEL - They thought he was nuts.

Scroll down to see exclusive content, including raw drone video, an interactive 360 image and photos from a day spent observing the people of Bell Works.

Investors, real estate agents, even his wife thought Ralph Zucker lost his marbles as he traveled around the state, telling anyone who would listen that he wanted to turn the abandoned Bell Labs building in Holmdel, N.J., into a powerhouse for the digital age.

Job-seekers! Here's advice from Bell Works companies on how to get hired

Zucker understood their skepticism. At 2 million-square-feet, it was the size of the Empire State Building tipped on its side. And Bell Labs was falling apart.

The lobby was overgrown with plants. The quarter-mile-long roof was leaking. Waves of millennials were leaving the suburbs and heading to cities with the promise of exciting jobs and a much cooler lifestyle.

With the project's reinvention price tag set at more than $200 million, they wished Zucker luck.

"Everybody sort of rolled their eyes, patted me on the back, offered me warm words of encouragement," Zucker said. "And probably as soon as I turned my back, their eyes … I could just hear their eyeballs rolling to the back of their head and saying, 'Boy, this is crazy.' I could get nowhere. I got nowhere."

A decade after Zucker took control of the property, his vision is fixed and focused. Bell Labs, the site of groundbreaking innovations from satellite communications to computer programming, is now called Bell Works, and it is finding new life.

Zucker's quest to save the historic building from the scrap heap of history is the result of persistence and sheer luck. The past 10 years he navigated New Jersey's notorious red tape; overcame anti-Semitic whispers; found an investor who owed his fortune to the place; and convinced chief executives from the Shore's fast-growing technology companies to stay in New Jersey and move there.

On Nov. 20, fast-growing software company iCIMS will become its biggest tenant, moving 10 miles from Old Bridge with 650 employees to serve as an anchor and designs for hundreds more.

They will join hundreds of other workers slowly populating the building, gathering in offices that are lined with whiteboards and filled with bells and whistles – space-age chairs, boardwalk-style basketball games, hammocks.

The leaky roof is being replaced with photovoltaic solar cells that will supply 15 percent of the building's electricity. The overgrown atrium has been cleared, replaced with modernistic furniture including edgy cylinders that, pieced together, create a couch.

"I think it's a grand slam success," said Peter Reinhart, director of the Kislak Real Estate Institute at Monmouth University in West Long Branch.

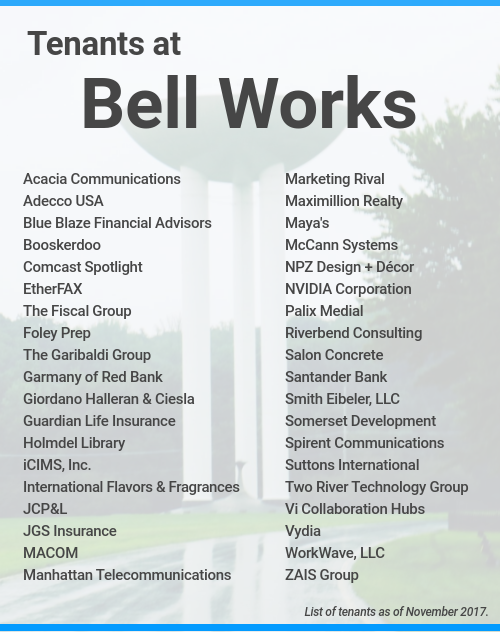

The building is more than 70 percent leased. It attracts rent higher than the state average. A steady procession of elected officials stops by for tours, eagerly aligning themselves with a symbol of New Jersey's economic resilience.

The result could be a game-changer for New Jersey, an economic afterthought since the internet bubble burst in 2001. Bell Works may very well become the blueprint to redevelop tired old suburban office parks nationwide.

"In terms of what they are doing, it’s fairly unprecedented," said Greg Lindsay, a senior fellow at the New Cities Foundation, a Montreal, Canada-based organization that studies development. "I don’t know anybody who has successfully revitalized something that empty of that scale."

This is the story of how Ralph Zucker saved historic Bell Labs.

Zucker, 56, lives in Lakewood with his wife, Denise. They have seven children and eight grandchildren.

He grew up in Baltimore. His father died of an illness when Zucker was three months old. And his mother remarried when he was nine, moving the family to Israel.

Zucker arrived in Lakewood in 1983 to attend Beth Medrash Govoha yeshiva. When he married a couple of years later, he bought a broken-down shack of a building and fixed it up with a group of friends.

The ceiling was just 6-feet-8-inches high, but to Zucker, who stands 5 feet 6 inches, it scarcely mattered. He had a place to live, and he decided he had a knack for turning dilapidated spaces into something better.

Not that it was easy. In the late 1980s, he bought a building on Monmouth Avenue and Fourth Street in Lakewood with two retail stores on the bottom and four apartments on top. Among the tenants was a cabinet maker who defaulted on his rent. Instead of payment, Zucker took over, running the business while the previous owner focused on making cabinets.

One winter, an automated valve that helped heat the building broke. He didn't have the money to replace it. So he sat in the cellar to manually turn the valve whenever it needed water.

Eventually, he saved enough to change the boiler. And he kept buying properties, including 17 acres in Lakewood to build the Village Park apartment complex. He obtained approvals from the town. He lined up an engineer, a lawyer and an architect. Then a recession hit, putting the project on hold.

"That was my first lesson: things that go up, go down," Zucker said. "You have to keep things going, and you have to pay bills. I got wiped out. I got wiped out."

Zucker got back on his feet, taking a sales job with Astor Chocolate, a company owned by his friend David Grunhut, and he picked up more business lessons. Among them: Deliver on your promise. When a customer complained about a delayed shipment, Grunhut would buy a seat on an airplane to get the chocolate there.

Zucker liked sales, he said, but his passion was real estate; he wanted to build things. So when the real estate market recovered, Village Park became viable again. He found an investor — a New York real estate family he declined to name — who agreed to put money not only into Village Park but also into a new real estate development company.

He called it Somerset Development after the intersection of Village Park — Somerset Avenue and East County Line Road.

And he began taking note of how people interacted with each other. Why, he wondered, did people have giant backyards when they spent most of their time out front, chatting with neighbors?

When his lawyer, Ray Shea, gave him a book called "The New Urbanism" by Peter Katz, it struck a chord. Suburban sprawl, which dominated New Jersey's development since World War II, was falling out of favor with younger generations who were tired of long commutes on crowded roads. They wanted to move back to cities, where they could walk places.

"He sees the entire chess board," Shea, a long-time real estate lawyer in Jackson, said of Zucker. "That’s rare. Some builders, they concentrate on just a portion of (the project). The return or yield on the investment. Ralph sees the whole chess board. How they are integrated and what moves he has to make to succeed."

Few office buildings symbolize New Jersey's suburban might like Bell Labs. The six-story building rises out of the woodsy Holmdel landscape, the sky reflecting off its mirrored exterior windows.

It was designed for AT&T's research and development laboratories by the renowned architect Eero Saarinen, whose projects include the IBM research center in Yorktown Heights, New York; and General Motors Technical Center in Warren, Michigan, that were suburban symbols of American wealth and innovation.

Bell Labs cost $20 million to build, or $167 million in today's dollars. It opened in 1962, a year after Saarinen died. And AT&T expanded it in the mid-1960s and the mid-1980s to its current size.

It was home to more than 5,000 employees, who worked on cutting-edge research and walked along corridors in hopes of chance encounters with their colleagues, fueling their ideas. If not, they could always smoke; ashtrays were built into the rails that lined the interior corridors.

"Bell Labs is probably the most important post-World War II building in the state of New Jersey," said Michael Califati, an architect based in Cape May. "It's not just the embodiment of Saarinen's great design abilities; it was also an example of New Jersey's prowess in the post-World War II era that spawned this great suburban state that we know."

The building brought a flood of highly educated, well-paid workers to the Jersey Shore and it turned Holmdel into an innovation epicenter. Bell Labs researchers paved the way for satellite technology; wireless phones; computer programming; and the internet.

Margo Tikijian, 54, of Fair Haven, was hired by AT&T in 1987 soon after she graduated from Indiana University, where she studied hearing sciences.

She developed speech recognition systems. She shared a private office with just one other co-worker. She dressed casually and set her hours. Her co-workers had doctorates, and a few, she said, had egos to boot.

"We were all in awe of each other," Tikigian said.

Listen to our exclusive interview with Margo Tikijian and Miriam Kotsonis, who worked at Bell Labs:

Their inventions, though, would haunt the company like a robot that comes to life in a horror movie and turns on its creator.

The glue holding it together — Ma Bell's monopoly — began to fray in 1982 when a federal judge broke the company up.

AT&T spun off its research division and its building in 1996 into Lucent Technologies Inc. Five years later, the internet bubble that fueled Lucent's sales of fiber optics collapsed. In 2006, it merged with a competitor, Alcatel.

Bell Labs' glory days were over, and they weren't coming back. The massive millennial generation was quickly coming of age, migrating to cities and taking high-tech companies with them.

Suburban office buildings were left stranded, and Holmdel had the biggest of them all.

When it came time for Alcatel-Lucent to sell the building, Zucker wasn't its first choice.

It agreed in 2006 to sell the 472 acres to Preferred Real Estate Investments of Pennsylvania, whose CEO, Michael G. O'Neill, proposed knocking Bell Labs down and building an office complex or homes.

"It is a crime we can't figure out a way to reuse this building," O'Neill told the Asbury Park Press in April 2006. "There is just no way. It is absolutely and utterly unusable."

But some Holmdel residents opposed Preferred's plan to build hundreds of homes. Others signed a petition hoping to preserve the historic Bell Labs building. Preferred and Alcatel-Lucent never closed on the sale.

"The public was just dead set against all of those (housing) units coming to Holmdel and knocking the building down," Holmdel Deputy Mayor Patrick Imprevaduto said.

A broker for Alcatel-Lucent called Zucker and asked if he was interested. By then, Somerset was redeveloping the former 140-acre Curtis Wright Aircraft Facility in Wood-Ridge, Bergen County, into Westmont Station, a transit hub with high-density housing and retail.

Zucker looked around the Bell Labs. It was gloomy with overgrown trees that had died, crushed cobblestone and barely any light coming through the skylight into the atrium.

Zucker saw something else. "I saw these great bones in this Saarinen building," he said. "Clean lines, a quarter of a mile long. Three football fields in a row. … I intuitively understood that if we could create the zoning, which was the challenge, then we could create the space."

More:Catch a glimpse of Holmdel's next-generation library in Bell Works

With Wall Street collapsing, Zucker agreed to buy the property, pending the town's approval.

He wasn't universally embraced. A flier on behalf of a candidate running for Holmdel council in 2009 warned voters that the town was on its way to mirroring "Zucker's urbanized Lakewood," according to a story in the Independent.

Holmdel resident Carol Beckenstein wrote a letter to the newspaper, saying the flier had anti-Semitic undertones. It called the development "Zucker" 12 times instead of by the company's name, Somerset Development, she wrote.

Zucker huddled with his public relations firm, Beckerman Public Relations, to figure out how to handle what was being unsaid: an Orthodox Jewish developer from Lakewood was a threat.

They decided to ignore it, Zucker said, heeding advice from his Astor Chocolate days: Make good on your promise.

"I think it’s a shame when we see a community try so hard to keep people out," Zucker said. "But it just puts the onus in a way on our community saying, 'Here, you have nothing to fear from us, and let's work harder to be good neighbors.'"

In 2009, Zucker decided to invite Holmdel residents and Bell Labs veterans to an open house, where they walked into the spruced up atrium, ate ice cream and listened to music from a jazz band.

He could see their faces light up. They could see what he saw. The building could be saved. The candidate opposing the project lost the election.

Zucker worked for four years to get government approvals – a period that included more setbacks.

At one point, Alcatel-Lucent took it away from him and sold it to another developer who promised to close the deal faster. A year later, the new deal fell apart. Alcatel-Lucent returned to Zucker, who purchased the property for $27 million.

And he made concessions. Zucker gave up his goal of creating a walkable community. The town rejected high-density housing. He sold 230 acres to Toll Brothers for $28 million, paving the way for 185 age-restricted townhomes and 40 McMansions.

Holmdel approved the project in August 2013.

Like a dog who finally caught the car he was chasing, Zucker could only ask: now what? He had repeatedly struck out trying to raise the $200 million he needed from investors to redevelop the building.

In New York, Josef Straus, the retired chief executive officer of JDS Uniphase, a Canada-based communications company, was visiting the opera, when he picked up a Wall Street Journal and noticed a story about the sale.

Straus, 71, of Ottawa, Canada, owed his career to the building.

In the late 1970s, he was a young physicist, specializing in what was then a little-known field of fiber optics and traveled to Bell Labs to give presentations to researchers. He returned home and excitedly told his wife about the brainpower that surrounded him.

Straus, who often wears a beret and has a personal art collection that includes a Monet, reached out to Zucker. He told him he was interested in investing in the project. They met over dinner. And Zucker won him over.

Straus declined to disclose the amount of his investment, other to say it "wasn't an inconsequential amount."

"It's more emotional than rational," he said. "Now it’s rational. But at that time I was really thinking this was an important thing to preserve and to keep and show. And I owe, personally, my technical past and the company’s success to the place."

The long odds didn't bother him. Straus often told colleagues, when you are in a boat in stormy weather, keep looking at the horizon so you don't get dizzy.

The parable was quickly put to use.

Zucker signed a lease with Community Healthcare Associates, a Bloomfield-based company that specializes in reusing hospitals, for 400,000-square-feet that would be used for medical offices. But CHA walked away after the two sides couldn't agree on their responsibilities, said Bill Colgan, CHA's managing partner.

Holmdel officials then reached out to 10 companies they referred to as white knights —Google, Amazon, Bloomberg, for example — but they struck out, too, Holmdel Councilman Eric Hinds said.

"We learned a lot from big companies, but we quickly realized this is suburbia New Jersey, Exit 114 (on the Garden State Parkway) south of the (Driscoll) bridge," Hinds said. "The appetite was not as big as we would naturally hope for."

With the Jersey Shore's economy trying to recover from the Great Recession and superstorm Sandy, Zucker turned to a simple idea: crawl, walk, run.

In the spring of 2015, Chris Palle and Sean Donahue were looking for space to create Vi Collaboration Hubs, co-working space that would bring together technology entrepreneurs who didn't have a dedicated office.

They asked Zucker, who had little to lose.

They set up shop in the cavernous building, rent-free, and worked, without power, as long as their laptops would last. They wandered the building, finding equations on whiteboards that had been frozen in time. And they sponsored meetups, bringing technology talent back to the building, if only briefly.

More:Thousands head to Bell Works in Holmdel to view solar eclipse

"I knew a little about Bell Labs, but educated myself quickly and started talking with some of the former guys as they came in and really understanding, wow, the past of this building is incredible," Donahue, 26, of Matawan, said. "But now, seeing the vision for the future, it made a heck of a lot of sense. This is meant to be here."

Zucker hired Alexander Gorlin as his architect and assembled the rest of his team. Among them:

- The Garibaldi Group, a Chatham-based real estate agency. Owner Jeffery Garibaldi said he took his son, Scott, and an intern to meet with Zucker as a courtesy, knowing that the project could drain his agency. “Three hours go by, I said, ‘Both of you are fired,’” Garibaldi said with a laugh. “I said I would come back with a proposal.”

- Co Op Brand Partners, a New York marketing agency. Paul Newman, the chief creative officer, convinced Zucker to change his first choice of a name, “Bell Place,” to “Bell Works.” And it created a brochure with images of the building, Albert Einstein, a giraffe and acrobats. On the inside, it touted Bell Labs’ eight Nobel Prizes. “It’s almost a secret sort of lab,” Newman said. “You want to keep intrigue about what’s behind those doors. It’s about your imagination.”

- NPZ Style + Décor, a New York interior design company. Owner Paola Zamudio began to decorate a handful of small offices with a mid-century hipster touch: tulips in small vases that adorn a wall; retro refrigerators from the Italian company Smeg; the pop art of Abraham Lincoln in a space helmet.

Zucker set up a small café in the atrium. It had comfortable chairs, a foosball table and a New Jersey Bell telephone booth.

The marketing team of Jennifer Smiga and Shannon Winning of Marketing Rival, tired of meeting clients at Starbucks, went to Bell Works in December 2015 and marked the occasion on Instagram with a picture of Winning, bundled in a scarf and coat, but smiling, the foosball table behind her.

More:Red Bank's Sarah Krug reinvents cancer care

By then, though, Zucker had signed his first lease: James Lavin Real Estate took 1,100 square feet in July 2015. Zucker asked Garibaldi if he was crazy to agree to it.

“We said, ‘You were crazy to do this in the first place, so be consistent,’” Garibaldi said.

Chris Sullens and Colin Day were among a group of technology leaders who gathered at the Asbury Park Press in July 2015 to talk about how to revive the Shore’s once-proud technology legacy.

Sullens, the chief executive officer of WorkWave in Neptune, and Day, the chief executive officer of iCIMS in Old Bridge, were leading companies that were quickly outgrowing their space. And there was nowhere in Monmouth County to go.

After meeting with Zucker, Sullens decided to take the chance. Many developers, he said, drove a take-it-or-leave-it bargain. Zucker seemed to have his focus on the big picture.

“You can tell when people are just behind something 100 percent," Sullens said. "They’re going to figure out a way to get it done.”

WorkWave signed a lease in May 2016, taking 72,000 square feet with an option for another 72,000 square feet, and bringing 185 employees. iCIMS followed two months later taking 350,000 square feet, enough to grow from its current 650 employees to 2,000.

More:WorkWave in Holmdel bought by Sweden-based IFS

The dam broke with household names and up-and-coming businesses. Jersey Central Power & Light and Vydia; The Guardian Life Insurance Co. of America and Atomic Veggie Studios; International Flavors & Fragrances and Springboard Public Relations.

Traditional lenders Investors Bank and OceanFirst Bank joined Josef Straus, a sign of growing confidence.

Bell Works’ rent is $30 to $35 per square foot, Garibaldi said. By comparison, the state’s average is $26.42 per square foot, according to data from Transwestern, a real estate firm.

The payoff for the Shore could be bigger. Vydia, a technology company that helps internet sensations get paid for their content, started in the Vi coworking space and expanded in January to its 4,500-square-foot office. It has 40 employees.

Among them is Rick Saporta, 36, of Neptune City, who was working in Manhattan, but has cut his commute to 23 minutes each way.

More:Vydia, Symbolic, Safe-Com: Top innovative Shore tech companies

"After two months I’m sitting in a café downstairs and all the construction stuff has been removed and I’m just staring," Saporta said, sporting a T-shirt, shorts, a beard and tattoos. "The sun is gleaming in from that glass roof. It’s absolutely gorgeous."

It vindicates Day’s decision. iCIMS signed its lease on a whim, he said, hoping the building would come together and help him attract talent. It would offer employees amenities that only the Googles and Apples of the world are big enough to provide on their own.

"We all very quickly calculated the risks and reward," Day said. "We couldn’t help but just land on the side of reward for this building.”

In Ralph Zucker’s world, nothing seems to come easily.

The weekend in May before WorkWave moved in, a pipe broke, flooding part of its office. About that time, the founder of Symbolic IO, a promising technology tenant, was arrested and charged with assaulting his girlfriend, an episode that had Holmdel police searching for him at Bell Works, according to police reports. He no longer is with the company.

Zucker said missteps are to be expected. He has traveled the state, trying to convince people that he can create an urban vibe in the middle of suburbia. With any city comes the good and the bad when you bring people together.

Can he save New Jersey or solve anti-Semitism? It's unlikely. He decided that all he can do is make good on the promises he made.

One day in May, Zucker was mulling the size and shape of new tables for a cafe in the atrium, down to the tiniest details, and a busy summer was ahead.

More:Holmdel's former Bell Labs in Oscars Cadillac commercial

He was nearing deals with a hotel operator, a wood-fired pizza place, a beauty salon. He was the guest of honor at award banquets. And he was giving tours, showing off his vision, searching for signs that visitors could see what he saw.

“Looking back, I don’t know,” Zucker said as construction workers in hard hats milled about the cavernous building. “I always felt good about this. Now I feel great.”

Design and development by Felecia Wellington Radel

Michael L. Diamond; 732-643-4038; mdiamond@gannettnj.com