Board of Trustees Votes to Keep Name, Requires Significant Steps Be Taken to Ensure Comprehensive Understanding of the Full Extent of Wilson’s Legacy

WEST LONG BRANCH, N.J. (June 24, 2016) – The Monmouth University Board of Trustees voted yesterday to retain “Woodrow Wilson Hall” as the name of the university’s central administrative building, while also requiring that significant steps be taken to ensure a comprehensive and balanced understanding of Wilson’s legacy. The decision comes after months of discussion, examination, and collection of feedback from faculty, students, and alumni, on the cusp of the 100th anniversary of Wilson’s residence in West Long Branch in the summer of 1916.

The Monmouth University Board of Trustees was charged with balancing Wilson’s demonstrated record of service as a college president, Governor of New Jersey, 28th president of the United States, Nobel Peace Prize recipient, and principal architect of the League of Nations with lesser-known, but well-documented, views on race and immigration that included denying African American students admission to Princeton University, re-segregating the federal government, and endorsing the Ku Klux Klan.

The trustees balanced Wilson’s legacy of achievement, against his racial intolerance in the context of the university’s educational mission and its core values: excellence in teaching and learning; empowerment of the university community; fostering a caring campus; integrity; diversity; and service. The Board felt that its decision to honor Wilson’s record of service, while simultaneously educating the community on his controversial positions, embodied one of the most basic tenets of a liberal arts education; deriving knowledge from complex issues that cannot be reduced to simple binary terms.

“I am proud that our entire Board chose to proactively examine Wilson’s legacy with the help of faculty, students, and staff members,” said Monmouth University Board Chair Henry Mercer. “From this we know that we have a responsibility to tell Wilson’s full story, the good and bad. This provides a valuable learning opportunity for the Monmouth University community.”

The move to reconsider the name of Woodrow Wilson Hall emerged from a broader exploration of race and inclusion initiated by Monmouth University President Paul R. Brown in early December 2015. The initiative on the Monmouth campus followed protests and tension at the University of Missouri, the University of Michigan, Yale, and at nearby Princeton University, which has been simultaneously grappling with Wilson’s legacy on its campus.

While there were no protests over Wilson on the Monmouth University campus, President Brown felt it was important to start a broader conversation on diversity and inclusion to better understand the campus climate through open discussion. As part of the campus-wide conversations, Brown also initiated efforts to educate the university community on Wilson’s legacy in its totality, and to solicit feedback on how the Woodrow Wilson Hall name influences the campus experience, and whether a potential change to the name would affect that experience.

Drawing upon the expertise of faculty experts and the university’s Office of Equity and Diversity, the university held open forums, small group discussions, individual meetings, and academic sessions. Survey feedback was also collected from the broader alumni population to better understand the connections between graduates and the university’s most recognizable landmark.

“A very common refrain from our alumni was that while Wilson’s racist views are abhorrent, he was a product of his time, and that judging the values of a previous era by our own standards could lead toward the path of erasing unpleasant facts of history, which is never an appropriate action for any academic institution,” Brown said.

Mercer added, “Studying history allows you to learn from past mistakes and do better. Understanding all the historical facts surrounding Wilson’s views gives us a teaching tool to drive forward the university’s core values of both diversity and excellence in teaching and learning. The work ahead is to promote tolerance and diversity on campus through open and honest dialogue.”

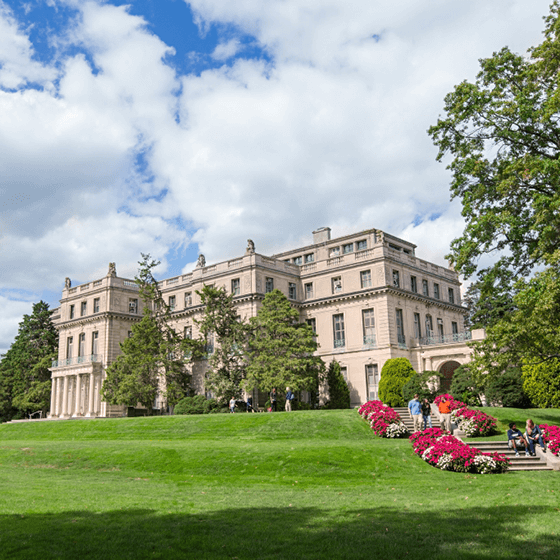

Wilson’s association with Monmouth University is widely misunderstood. In fact, Wilson’s connection to Monmouth University is largely geographical rather than personal. The current administrative building that bears his name was not built until after his death. During his 1916 re-election campaign Wilson did spend about six weeks in the first Shadow Lawn mansion, which burned to the ground in 1927.

The second Shadow Lawn mansion, erected in the footprint of Wilson’s Summer White House, was acquired four decades after Wilson’s stay in West Long Branch. Despite the lack of a meaningful connection to Wilson, most alumni take pride in the campus’ association with a national historic figure, and report being largely unaware of Wilson’s controversial views and actions.

The current Woodrow Wilson Hall has had several names since it was constructed in the late 1920s: Shadow Lawn; The Great Hall; and Woodrow Wilson Hall—on more than one occasion. A curious fact of the building’s name over the past century is that it was named Woodrow Wilson Hall when Monmouth acquired the property from Highland Manor Junior College in 1955, and was renamed as The Great Hall, only to be rededicated as Woodrow Wilson Hall 11 years later.

Moving forward, the board charged the administration with sharing a more complete view of Wilson’s history as part of a collective learning process about the historical issues of his time, and identifying ways to ensure a comfortable and inclusive experience for all campus members.

University administrators will work to identify ongoing efforts including: comprehensive visitor education through building and campus tours and brochures; finding ways to honor the contributions of Julian Abele, one of the first professionally trained African American architects, who was responsible for Wilson Hall’s interior design; and creating a living history space in the building and related educational programming.